The Searchers and The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

Written by Mario Martin on 8/7/2024

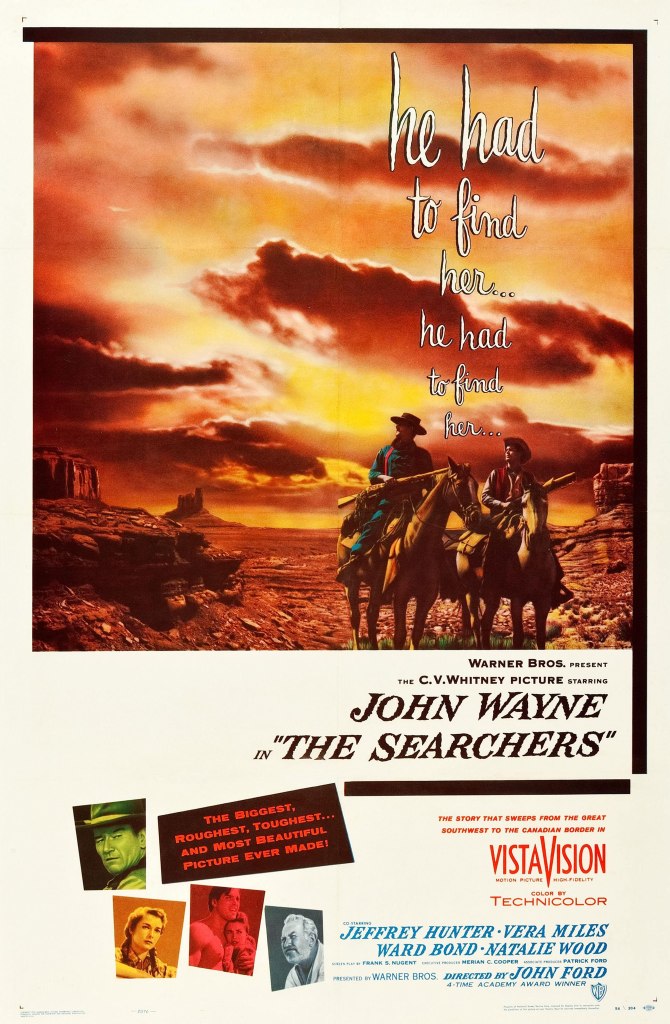

Being as they are the first Westerns I recall watching in my formative years, I felt that it was appropriate to start this blog with a double feature of John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966). The first time I had seen the former was in 7th grade towards the end of the year when there was no class work and the teachers would roll in the TV to show a movie. For my 7th grade science class we watched The Searchers. It was one of those films, especially for my naive, adolescent mind, that seemed so far above what I knew cinema to be. I had never seen a picture in Technicolor, or one made by such a significant voice. It was my first exposure to John Wayne and I was enraptured.

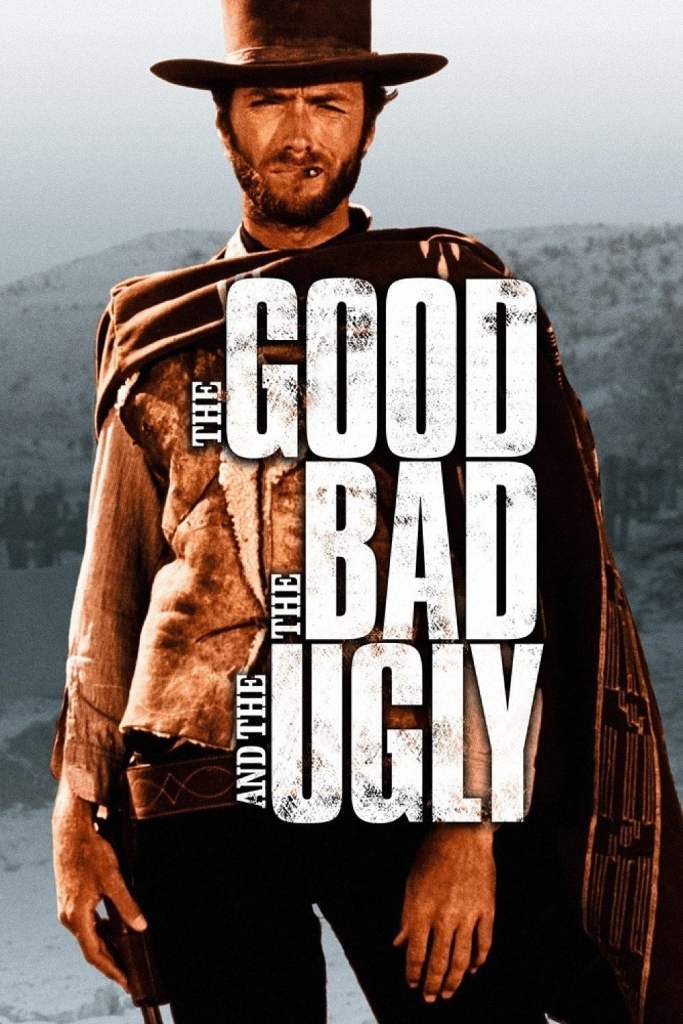

As for Leone’s picture, my connection to it stretches back to about when I was six, and had my stepdad’s poster of the film framed and hanging in my bedroom. Every day I looked at that poster, and that image of Clint Eastwood and started making up my own stories of what this movie was. Stories about how the man on the poster was actually my Uncle Richard, and despite having not seen the picture for awhile, I had endless stories about it. I think I ultimately ended up watching the picture in its entirety on TV when I was about 12 or 13. Around the same time as The Searchers now that I think about it!

At this point in my life, I knew that I am Native American and what the history of America was like when it came to the relations between the settlers and the indigenous, but had very little connection to it outside of the occasional sweat ceremony and the Indigenous art my mom always kept around. But for this film, I also acknowledged the savagery of everything that I saw. That image of John Wayne riding his horse out of Chief Scar’s tent with his bloody scalp in hand incredibly disturbed me, but my ignorant mind could only see that a film from the 50s went to such a brutal place, and that was cool.

So as time went on, I always remembered the picture but naturally my taste developed with age, as well as my self awareness. As such, I stumbled upon a very small and recent discussion on Twitter or Reddit or something of that sort, with the original poster having claimed “how unwatchable The Searchers is” and that brought me to wonder how that may be. Long story short, it’s a very unpleasant but very important film but that’s not what this post is about.

Regardless, that’s the end of my saccharine nostalgia dump on my connection to those films. The point of this blog as well as this post is to identify how the years surrounding the production of these films may have affected the directorial sensibilities as well as the narrative and themes. Additionally, my big idea is that the Western isn’t so much a genre, as it is a pastiche for various filmmakers from all over, to break down American values and traditions as well as the history of the country. Naturally, how do these two films find their place within all of this?

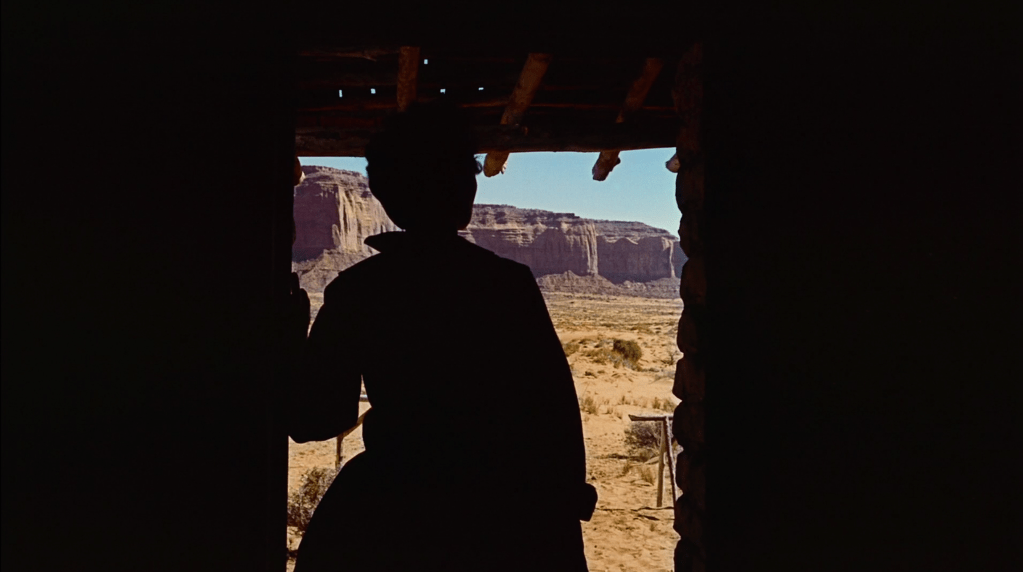

What John Ford sought to do with The Searchers was re-contextualize the myth of the American West, the self righteousness of the Manifest Destiny and the relations between the settlers and the Native American nations. What’s common in Westerns as well as the myth of the outlaw is that these figures were often Confederate soldiers after the conclusion of the Civil War. They felt that they had no place in the Union as well as the ever changing modern society. So they drifted, doing odd jobs going town to town to make a living. In the film, we first meet John Wayne’s character Ethan Edward’s riding up to his brother’s house, the camera shooting through a doorway to frame his introduction as the crossing of a threshold.

Doorways and the general crossing of thresholds are a major theme within this picture. As Ethan had been wandering for three years after the surrender of the Confederate States, he’s effectively reentering society for the first time by crossing through the doorway into the Edwards’ home. Ethan shows up with freshly minted coins, and a medal from his service in the Second Franco-Mexican war. A later statement from the Reverend and Ranger Captain Clayton implies that Ethan wasn’t even present at the Confederate surrender. These elements establish Ethan as a deeply traditional man, stuck in his ways and too stubborn to accept any new development or growth.

We’re soon introduced to Martin Pawley, Ethan’s adopted nephew who is of 1/8th Cherokee blood, information that causes Ethan to condemn him as a “half-breed” and a variety of other slurs. However, an interesting point is that while Martin certainly isn’t without his flaws, he acts as the moral compass throughout the film. He apologizes to his aunt Martha for showing up late for supper, tolerates Ethan’s abuse but nonetheless willingly helps him at every turn. Otherwise pretty small aspects of his character, but Martin matures while maintaining this orientation and never falters in the face of Ethan’s deep hatred.

The conflict of the film arises when Chief Scar, a Comanche war chief, leads a murder party to burn down the Edwards’ ranch and kill all but the two daughters, Debbie and Lucy who were kidnapped, while Ethan and Martin were away searching for missing cattle. Upon their return, Ethan and Martin grieve and while Ethan prevents Martin from seeing the corpse of his aunt Martha, this sudden act of humanity could also be misconstrued as a deliberate act of bigotry against Martin. Ethan had a very close relationship with his sister in law, and certain visual clues implied a more complicated relationship (Ethan having been gone for eight years and Debbie being eight years old either being a major clue or coincidence). But earlier, while Ethan, Martin and the rest of the crew were searching for the cattle, Ethan and Martin have this exchange where Ethan tells Martin that he’s not his uncle. “Don’t call me uncle, I’m not your uncle…” which coming from Ethan very much exclaims Ethan’s desire to have no relation to Martin whatsoever. He lacks empathy and respect for the young man and he wants him to know that. As such, Ethan’s attempt to keep Martin from seeing the corpse of Martha certainly feels like it comes from that same patronizing side of Ethan.

Going back in time a bit, when the Reverend Captain Clayton sees Ethan again for the first time since the war, Clayton offers to swear Ethan in as an active Texas Ranger to pursue the missing cattle, to which Ethan remarks “that wouldn’t quite be legal” which raises several eyebrows as to Ethan’s own skewed sense of morality. The interesting aspect of this is that while throughout the film, Ethan grows to respect and even accept Martin, all of his character traits are on display from the start and we watch as Ethan’s brutality grows more and more savage as time goes by. By his side through it all however is Martin, who’s always the voice of reason, even at one point claiming that he has to stay with Ethan while they search for Debbie and Lucy because he knows what he’s capable of and wants to be sure that he’s by Ethan’s side to snap him back to reason once he inevitably cracks. With all of this complex characterization, John Ford and screenwriter Frank S Nugent break down the image of the outlaw cowboy, the western hero, the idol of the Wild West that we’ve grown to admire and sanctify and make him nothing more than a deeply flawed human with major flaws. The true hero of this story would be Martin for without him, Ethan would’ve gone on a murder path and the original goal of bringing Debbie and Lucy home would’ve failed. With Lucy already dead and Debbie by the end of the film being one of Scar’s wives, Ethan was ready to see Debbie die in order to exact his revenge against Scar. But more on that later.

An interesting point to make here is that with Martin being of mixed race, not only is he the moral compass but is also the middle ground in this overall theme of miscegenation within the film. To Ethan, Marty is Native, even with only ⅛ blood. To the Natives of the film, Marty is another white man. It’s interesting to see that Ethan is more educated on the cultures and customs of the Comanche, even being the one to speak the language and translate on behalf of Marty. One significant example that puts Ethan’s knowledge into play as well as demonstrating this theme of miscegenation is when the two find themselves trading supplies with a local tribe, only for Marty to find out that he accidentally traded for a wife. Marty reacts to this in a frustrated manner, with Ethan educating him on the fact that if they simply “sent her back” it would cause the ire of her family and they would be after them. But throughout this whole ordeal, Ethan is the one who will translate for the woman who has said her name is “Wild Goose Flying Through the Night Sky” but chooses to answer to “Look” since Marty constantly pleads with her by saying things such as “Look, I wish I could make you understand.”

But we find out about this ordeal through a letter Marty has sent home to Laurie, his childhood sweetheart who’s romantic interest in him he’s fairly ignorant of. A later plot point in the film is Ethan and Marty breaking up Laurie’s wedding to Charlie McCory, a local guitar player and the one to deliver the letter to Laurie. But quantifying Marty’s relationship to these two women, Look was the one he had unintentionally married and didn’t end up with Laurie until the very last shot of the film. But with Marty being mixed, this is a way of him acting as that middle ground between the whites and the Natives. Additionally, the introduction as well as Marty’s mistreatment of Look for the most part acts as a sort of turning point for Ethan, where it seems like he’s starting to see the indigenous as human. He laughs at the situation of Look all of a sudden joining their group, but respectfully (albeit sarcastically) refers to Look as “Mrs. Pawley” and treats her as he would anyone else’s wife. He laughs when Marty kicks Look down a hill in frustration, but follows that up with the proclamation that that action would be grounds for divorce in Texas. Again, sarcastically but nevertheless acknowledging the abuse Marty has committed.

However, not long after this we see Marty and Ethan hunting for food, finding a herd of buffalo that is widely known to be a major source of food for Native Americans. While they successfully shoot one down, in a manic rage Ethan begins shooting at the whole herd claiming that “killing buffalo is almost as good as killing Injuns.” By this point, it’s clear that Ethan’s motive is genocide. It’s not often that Ethan even brings up Debbie anymore, but he always mentions wanting to look for Scar. But not long after this episode, the bugles of the American cavalry sound off in the distance and we see their uniformed presence riding across the screen. From here, we immediately cut to the decimation of a Comanche camp, with corpses strewn across the ground and an American saber left stabbed into the torso of a cadaver. This juxtaposition serves as a very major acknowledgement on behalf of Ford that the perceived “cultured and organized” American military is just as complicit in the savaging of Native Americans as the mythology of the Wild West has led us to believe the Natives are capable of. At no point do we see the Comanche committing more savage atrocities than the white settlers, and if anything the Comanche motivation is more just. Historically, we know their land was illegally taken, treaties often being broken for the sake of “westward expansion” and indigenous action was more or less retribution for what otherwise would be considered grounds for declaring war. The White American justification for the rape and murder of the Natives? “They’re there and they’re savage. They’ll get us if we don’t get them first.” This anticipatory behavior undercuts the whole film with Ethan on his revenge path but largely only worried about Debbie being turned into a tribal wife because at that point, she’s no longer human in his eyes.

It’s at this point where Ethan and Marty search through the remnants of the camp and Ethan finds the body of Look. He covers her in her blanket and calls over Marty to see the body. This parallels Ethan finding the body of Martha and not allowing Marty to see. Does Ethan show him Look’s body because he respects Marty more and is now showing signs of humanity? Or is it because he sees Look’s death with less value than Martha’s and by proxy is more willing to allow Marty to see? Admittedly, I jump back and forth between these two questions because one one hand, it’s clear that Ethan is still on a warpath and still barely sees indigenous people as human. However, this also parallels Martha’s death because with their relationship being suspiciously close, he sees the death of what is legally Marty’s wife as something with the same levity. As such, the first major display of grief towards the death of a Native acts as another such turning point in Ethan’s development into humanity. Additionally, Marty’s proclamation that Look was harmless and didn’t deserve to die incriminates the senseless actions of the White Americans and puts us in this complex gray area where we may not agree with the actions of either side, but we also acknowledge that both sides have lost lives and that’s worth a level of grief and empathy.

The rest of the film continues with Ethan and Marty finally finding Scar’s camp in New Mexico, and seeing that Debbie, now 14 years old, is one of Scar’s wives. In this scene as well, we learn that Scar has lost sons to the white man, and claims that “for every son, I take many scalps.” This paints this mirror image between Ethan and Scar that is present in various moments throughout the film. Albeit, Scar’s actions comes off as the more civilized since he’s acting within the realms of his culture, while Ethan is stubborn and refused to be present at the Confederate surrender, disappeared for three years and acts out of personal interest instead of thinking of the well being of his family.

So Ethan and Marty pull back, satisfied that they found Debbie but lamenting her perceived loss of “white virginal innocence” by becoming Scar’s wife. However, Debbie shows up to their camp and acknowledges that she does remember Marty, but demands that they run because she’s with her people now. This infuriates Ethan who raises a gun to Debbie, Marty standing in between (again, the literal and cultural middle ground between white and Native). This action makes it clear that Ethan no longer sees Debbie as human, and proves that his motivation was genocide all along. She is saved when an arrow strikes Ethan and Marty grabs him and they ride off, getting in a gun battle before they retreat home.

Once again crossing through a cultural threshold, Ethan and Marty return to Texas to find that Laurie is getting married. With the two having been gone for the better part of five years, they’re now reentering society from the wilderness. Upon seeing that Laurie is getting married, Marty pleads for her hand and comes to blows with Charlie which is essentially a battle between the wilderness hardened man and the city man. Additionally, this is another flip flop instance of Marty being in the cultural divide and wanting to be in a relationship with a white woman. Marty wins the fight and effectively ends the marriage to take Laurie for himself, but this also comes to a halt when the military comes to request Reverend Captain Clayton and the Rangers’ assistance in hunting down a nearby camp led by Scar.

Now, the interesting thing is that it is a Lieutenant that comes to request Clayton’s help, but is such a fresh faced boy that he might as well have been just a child. His obsessive desire to speak in that official military manner prevents him from communicating like a human, and it’s learned that his father is a higher ranking official so this is also a good case of nepotism. Regardless, Ethan and Marty know that Debbie would still be with Scar so they choose to join the Rangers. However, this is much to Laurie’s chagrin as she now sees herself as Marty’s woman, and here he is disappearing to find Debbie once again. But it comes as a shock when Marty once again acknowledges that he knows Ethan will just have her killed, and Laurie responds that Debbie is now a Comanche, and Martha would’ve wanted Ethan to kill Debbie. Because for most of this film we’ve seen the off putting and savage minded Ethan express this sentiment. Now we’re getting the sweet Laurie, who seemingly always had good intentions, parrot this sentiment which shocks Marty. This scene incriminates not just who we could dismiss as backwoods country folk as the bigots, but also the kind girl next door which doesn’t make it any different as it’s all bigotry.

But ultimately, we see Ethan, Marty and the Rangers get ready to raid Scar’s camp, while also seeing Scar’s perspective to establish a mirror to the murder raid at the Edwards’ ranch. Marty demands to rescue Debbie as he knows that they will kill her once the raid shows up, to which Ethan says that he’s counting on that happening. Regardless, Marty sneaks into the camp to rescue Debbie, but the alarm is sounded when Marty shoots an unseen Comanche to defend Debbie, and the Rangers proceed to raid the camp. As mentioned before, we see Ethan cross another literal and metaphorical threshold into Scar’s tent, where he proceeds to scalp his cadaver. Beyond the metaphorical threshold crossing, Ethan also ducks out of sight to commit an act he perceives as savage that neither we the audience see, nor the Rangers accompanying him. All we see is him riding out of the tent with Scar’s bloodied scalp, only to see Debbie and chase her down.

But with this conclusion, the turnaround for Ethan to grab Debbie only to pull her into an embrace seems oddly hasty. The small instances of character growth we see on Ethan’s behalf doesn’t seem to justify this quick of an acceptance. However, it might have taken Ethan a lot more work to get to this point if his motivation was to rescue Debbie to start with. He achieved his catharsis. Scar is dead and scalped so now Ethan doesn’t have anything to fight for. He welcomes Debbie and brings her back home, with that famous final shot that parallels the first. The family returns home but Ethan stays outside. To quote my good friend Jason, “he can’t live with who he was and he can’t live with who he’ll be so he just stays outside.” Thus, the final threshold isn’t crossed and the door closes not just on Ethan, but also on this mythological image of that outlaw cowboy. The times have changed and there’s no room for him.

An aspect I chose not to address simply because I don’t have a whole lot to say on it was the hypermasculinity of this cowboy image. It’s present in all Westerns and ever so present in this one as it’s something John Ford also approached. Ethan on the surface is the strong stoic type. He’s always in control, he always knows the way and if he doesn’t he’ll find his way. He’s very solitary and very off putting but gets the job done. Often, these types will save the day and get the girl, as was the case with John Wayne’s character in John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939). However, Ethan for all intents and purposes loses his woman at the beginning. If we’re to see Martha as the woman he wanted but couldn’t have, and Debbie as his either literal or surrogate daughter, the obstacles in place in this film prevent him from getting his girl or conquering the woman in the way that’s typical in such a hypermasculine society. In a way, Debbie is the one who got conquered by the tough and stoic, but long haired and more feminine appearing Native which breaks this masculine mold of Ethan’s image. Additionally, Ethan often cracked under pressure. He got too aggressive and too angry, and his furor got in the way of his and Marty’s mission more than it helped. With the assistance of others, the two recovered Debbie, so therefore there just simply isn’t a place for Ethan’s hypermasculine ego in the ever changing times within the context of the film as well as the context of America in the late 1950s.

Now, there’s an argument to be made that The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly is an end of life, Golden Age Western. The sentiment differs a lot and this serves as one of those pivotal examples of how Westerns as a whole changed in 1967 with Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch but that’s for some other time.

With TGTBTU, we follow three different personas with varying comprehensions of morality as well as varying justifications for their actions. With Blondie, who resembles “The Good” in the title, he fits this image of the solitary, stoic cowboy who may have a troubled history but nevertheless acts out of good intentions.

He dons a light colored coat and a light colored hat to parallel with the black hat and coat of the antagonist of the film which we also see with Lee Van Cleef’s character “Angel Eyes” who represents “The Bad” in the title. This is an image established within roughly 50 years of Western cinema (depends on who you ask when Westerns started). This is an image popularized by the likes of John Wayne, Alan Ladd, Randolph Scott and Montgomery Clift just to name a few. This all comes into play with the portrayal of Blondie within this film.

The irony in all of this is very striking, as when we’re introduced to Blondie, he’s chasing down a criminal named Tuco who represents “The Ugly” in the title. Tuco is wanted for multiple crimes and Blondie captures him and takes him in. It’s important to note that Tuco is immediately introduced with his title card referring to him as “The Ugly” the second he’s introduced.

Angel Eyes is introduced and we’re uncertain as to what his goal and intention is until he murders an innocent man for money, claiming that when he’s paid he sees a job through. Well, this mark offers him more money to go back and kill the man who hired him, so with Angel Eyes effectively being paid for a second job, goes back to kill his employer. It is here where he’s introduced with his title card of “The Bad”. This is significant, because once Blondie has taken Tuco in, and Tuco is about to be hanged, we watch as Blondie shoots the rope and rescues Tuco. This is all a plot for Blondie to keep making money, and now Tuco’s bounty is worth more so they’re just going to split the profits. It is here where Blondie gets his respective title card of “The Good”.

An interesting thing to point out about the background of this film is that Sergio Leone was a history buff. He had always thought of the American Civil War as a totally pointless conflict that was absurd and devoid of any good cause. He was also struck by the common knowledge of the war crimes committed in the Confederate POW camps, despite the knowledge that the Union POW camps were structured in a similar way. This is important to note that while we obviously consider the Union the morally sound side in this conflict, what with them being the victors and the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, that there was money in this war and at the end of the day, all of these lives were worth currency. Tuco, while being a convicted criminal on the run, isn’t introduced as “The Bad” only as “The Ugly,” because his motivation throughout this film is survival at whatever the cost. Angel Eyes serves the dollar, so his selfish capitalist greed is the “bad motivation” but Blondie is good, because while he’s also only driven by money, no one “gets hurt” in the process. However, his financial success is based on the support of evil people whether he’s complicit or not. At the time this film came out, we were past the Gulf of Tonkin conflict in Vietnam, but just a couple years before the Tet Offensive. America was involved in Vietnam, the Korean War had ended, and the CIA had supported one or the other side in multiple revolutions in Central and South America. The Cold War was very much a war of profit, and it seems that Leone was very conscious of that fact in the making of this film, especially in his portrayal of the conflict between the Union and the Confederacy.

This brings me to an important point in that most Westerns often took place after the Civil War. Much like with Ethan Edwards in The Searchers, these outlaw cowboys were often southern boys from the Confederacy just looking for financial opportunities. But that doesn’t discredit this film as a Western of course, because it so clearly is. Which feeds into my ever bigger point in the making of this blog is that the Western is less of a genre with its trappings and structural rules as it is a pastiche. What would make a film like this a Western over a film like There Will Be Blood (2007) or Buster Keaton’s The General (1926).

Is Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) a Western or a historical drama? Ernest Burkhart is a soldier returned from the Civil War after all, albeit from the Union. Is Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) a Western when the times it’s depicting happened 20 years prior? That would be the equivalent of a film in 2024 being made about the rise of the internet or Y2K. Point being, there’s a lot of things to consider when deconstructing a film as to whether it fits within the Western umbrella or not, and I suppose that’s the point of this blog.

Returning to the film, there was an interesting parallel between this film and The Searchers. In both films, the Union/American cavalry are often introduced intercut with images of savagery or criminal action. In the former film, we see the desolation of a Comanche camp, in this film we cut between horse hooves and Tuco’s gang on the hunt for Blondie in the same town. Before this point, Blondie was planning on pulling another scheme with Tuco, but Tuco wanted a bigger part of the profit since his life was on the line. In return, Blondie takes all of the money and sends Tuco walking 70 miles through the desert with no hat and no water. The actions of the morally just I think not, but I’m sure it wouldn’t take too much to justify that treatment of Tuco based on his criminal history despite Blondie having helped him escape on multiple occasions.

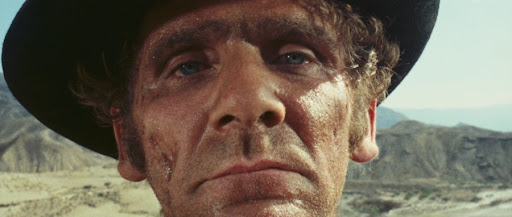

This action gets returned to Blondie, when at some point Tuco captures him and wants to take him through the desert. This time, 100 miles with no hat and no water. Blondie is now being tortured in the same way he tortured Tuco, but how do we feel differently about this? Despite Blondie’s questionable morals, we as the audience see him as the protagonist throughout the film, rooting for him all the way even when he takes advantage of the trust people place on him. Cinematically, we suffer with Blondie, watching as the skin of his face becomes cracked, his begging for the water that Tuco washes his feet in, and ultimately passing out, but we skip past Tuco’s same ordeal. Were we to watch Tuco trudging through the desert as we did Blondie, would we feel differently about Blondie’s actions? This comes as a pointed accusation towards media culture and propaganda with the skewing of narratives. Knowing that Leone was considering the lack of knowledge on what occurred at Union POW camps, it feels as though he’s making a point towards the portrayal of war crimes committed by “the other side” while ignoring the same war crimes the side we support have most definitely committed as well. The dichotomy between these two filmmakers is interesting, as John Ford was an American boy who served in the U.S. Navy during WW2, and as such his portrayal as savagery comes off as through the perspective of someone who may have committed it himself. Leone on the other hand, was an Italian boy who was too young to serve, and grew up watching his home country get decimated by the crossfires of war. It’s less so the justification or villainization of one side or the other, but more so convicting both sides’ actions and how they affected innocent civilians.

But at this point of watching as Blondie and Tuco make their way through the desert, they’re introduced to the narrative that we’ve known about since Angel Eyes was introduced. There’s $200,000 in Confederate gold buried somewhere that’s ripe for the taking. Angel Eyes has been pursuing this gold the whole film, but now Blondie and Tuco are introduced to it with the words of a dying Confederate soldier. He tells Tuco the name of the graveyard, and he tells Blondie the name on the grave. So now, Tuco no longer treats Blondie as his prisoner but now as his compatriot because without the other, neither will get the gold.

Soon after we’re introduced to Tuco’s history when we meet his brother who is the head priest at an out of the way chapel that hospitalizes soldiers from both sides. Blondie gets nurtured back to health, and we see Tuco’s relationship with his brother. From Tuco’s perspective, his brother abandoned his impoverished family for the church, which drove Tuco to rob and steal to provide. This moral distortion has been apparent throughout many different nations affected by war, Italy being one of course. For those who have seen Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), the desperate desire to provide for your family in times of impoverishment may drive someone to criminal actions, but is it so bad if it’s being done for the sake of other people? As such, Tuco’s behavior becomes a lot more deep and complex, for as criminal as Tuco may be he wears his motivations on his sleeve. He may lie and pander to get what he needs, but now we question if Blondie is any different from him.

We’re soon introduced to the Union POW camp when Blondie and Tuco, disguised as Confederate soldiers, get captured by patrolling cavalry. It is here we see Angel Eyes again, but as a Union officer. “The Bad” as a commissioned officer within the Union? The truth is not so subtle anymore. When before, Tuco and Blondie arrive at a Confederate camp seeking medical attention, but they get turned away since “we’re pulling out anyways and you’re looking for a medic?” The Confederacy has effectively turned their own away, and we see the Union beating and robbing their soldiers. As such, Angel Eyes takes Tuco in to feed him, and ultimately beats the truth out of Tuco as to the name of the graveyard where the gold is buried. While Tuco is being beaten, and everyone at the camp is very educated as to what is going on, we watch a sorrowful performance of a song from the POWs. Only for Blondie, who also gets taken in by Angel Eyes, is told that it would be pointless to beat him since he wouldn’t give the answer anyways. Additionally, there comes a point where Tuco meets a Union soldier without an arm, and remarks on his own bounty, “$3,000 is a lot for a head, I bet they didn’t even pay you a penny for your arm.” Again, the truth is no longer subtle, as it’s obvious that America focuses so much time and money on what it considers prisoner reform instead of investing money in the aftercare of their troops who have returned from home having lost a limb or lost their minds. This is the case now and it has been the case since 1966 and even before.

Nevertheless, we then see Angel Eyes and Blondie, with Tuco separate, arrive at a decimated town. One of those civilian towns caught in the crossfire of Union and Confederate fire and the town is totally barren. It’s unknown if there’s any civilians that remain, but Angel Eyes lays down for a nap in bed in a demolished building, with Blondie petting a kitten. Angel Eyes sends Blondie and one of his guys to look for supplies, with Blondie ultimately killing the goon that was sent with him. He soon meets up with Tuco again, and they band together to fight off Angel Eyes’ gang and work together once more. They take out the gang only for Angel Eyes to have disappeared, and they pursue.

We then get a lengthy and important set piece, where Blondie and Tuco happen upon a Union garrison on the shore of a river. With the Confederacy on the other side, the two fight over control of a small bridge over the river. All of the Union officers in this garrison are drunk and ready to die for their cause, with the Captain remarking that he wishes the bridge would just blow up. Since both sides want control over the bridge, with the bridge no longer gone they wouldn’t have anything to fight over. Lives would be spared and more people could go home to their families but nevertheless, the Captain acknowledges his thought is ground for a court martial so he would risk his life regardless.

What struck me with this viewing was the ways Leone photographed the faces of the soldiers in these trenches. They looked broken, desperate, the kinds of faces we’re familiar with seeing in WW1 and WW2 documentaries. These were the faces of men who lost the desire to fight for this unseen cause, and acknowledge that the war they’re fighting is pointless. Ultimately, Blondie and Tuco sneak across the river and under the bridge to rig it to blow. But before they set the charge, Tuco wishes to exchange their halves of the secret to the gold. Tuco gives Blondie the name of the graveyard, and Blondie gives a name to a grave. They set the charge and flee, the Union Captain with his dying breath watches with a smile as the bridge explodes.

As Blondie and Tuco wake up to a completely empty battlefield, we finally get the grand catharsis (after a bit more betrayal of course) where the two find the grave and dig. Tuco questions why he’s the one digging while Blondie watches when Angel Eyes shows up and also commands Blondie to dig. It is here we find out that even though Tuco truthfully told his half of the secret, Blondie did not. There was no gold in that grave, and Blondie admits to lying. The three line up for a classic shootout, with Blondie saying that he will write the name on the bottom of a stone. An important thing to point out is even though the shot is in a very wide master, we can tell that Blondie shot Angel Eyes, Angel Eyes at Blondie, and Tuco at Angel Eyes with Angel Eyes taking the fall into a freshly dug grave. However, despite Tuco still choosing to side with Blondie, Blondie had taken the bullets out of his gun the night before. Again, Blondie supposedly being “The Good” and being the morally just, the protagonist, the one we root for, he has continuously taken advantage of the trust people have placed on him to get to this place.

They finally dig up the gold and Blondie and Tuco split it two ways. However, as a game Blondie nooses up Tuco and rides off as a play into how their relationship started. The film ends with Tuco panicking, Blondie ultimately shooting the noose, and Tuco falling face first into his pile of gold. Tuco gets his gold, but Blondie wants to have his fun first.

But that’s the end of the film. However, with the gold being dug in fresh military graves, Leone’s concern with how the powers that be profit off of the corpses of innocent and often nameless soldiers seems ever so prevalent. There’s literal money in these graves, and the graves are desiccated for the profit of these individuals with questionable morals and intentions. Our heroes get the money, the enterprise and the profit, but largely at the cost of numerous lost lives.

The final connection between these two films being that, although we’ll have a mythological image of a hero of the Wild West, they often come with questionable intentions and are often on a warpath that affects the innocent lives around them. Reflective of American diplomatic relations, both of these films make a point to use the image of the cowboy to criticize American values and the agency it places on its history. It was often off of the backs of immigrants, women and natives but the acclaim wrongfully went to the ones who sow discord and profit off of the result.

The Searchers was watched on the Warner Brothers blu-ray release, and The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly was watched on the 20th Century Fox “The Man With No Name” Trilogy Box Set blu-ray release.