The Wild Bunch

Written by Mario Martin 8/14/2024

“We’ve got to start thinking beyond our guns. Those days are closing fast.” – Pike Bishop

The year was 1913. In the border town of San Rafael, a group of children gleefully watch as a horde of fire ants consume a scorpion all within a chicken wire cage. Behind them, a group of Army men ride into town, stopping to smile and wave at the townspeople, and even stopping to help an elderly woman who dropped her handbag. Under a tent, a pastor gives a sermon to a temperance union who then picks up their signs and marches the streets. These army men stop into a Starbuck railroad office/looking over their shoulders, and then stick it up. Here we meet the titular Wild Bunch, led by the aging outlaw Pike Bishop. On the rooftops outside, we also see a group of bounty hunters in wait, led by Deke Thornton who has been hunting down this gang, with a particular grudge against Pike.

The robbery goes down, but not before Tector, who is outside with the horses on look out, spots the glare of the sun off of the barrels of the hunters’ rifles. A shootout between the Bunch and the hunters ensues, with the civilians and marching temperance union caught in the crossfire. The ambush whittles down the Bunch’s numbers by half before they make it out of town, but they escape nonetheless. Fleeing to safety, the surviving members of the Bunch count their loot only to find out the bags of currency they stole were filled with iron washers. Tector’s brother Lyle turns to Pike, accusing his waste of time with the planning and the plotting only for them to make out with a dollar’s worth of washers. With Dutch and Old Man Sykes on Pike’s side, the old vanguard if you will, the Gorch brothers and Angel all come together in laughter at the misfortune. This error may be on Pike’s head, but what a mistake to make. So they laugh it off and move on.

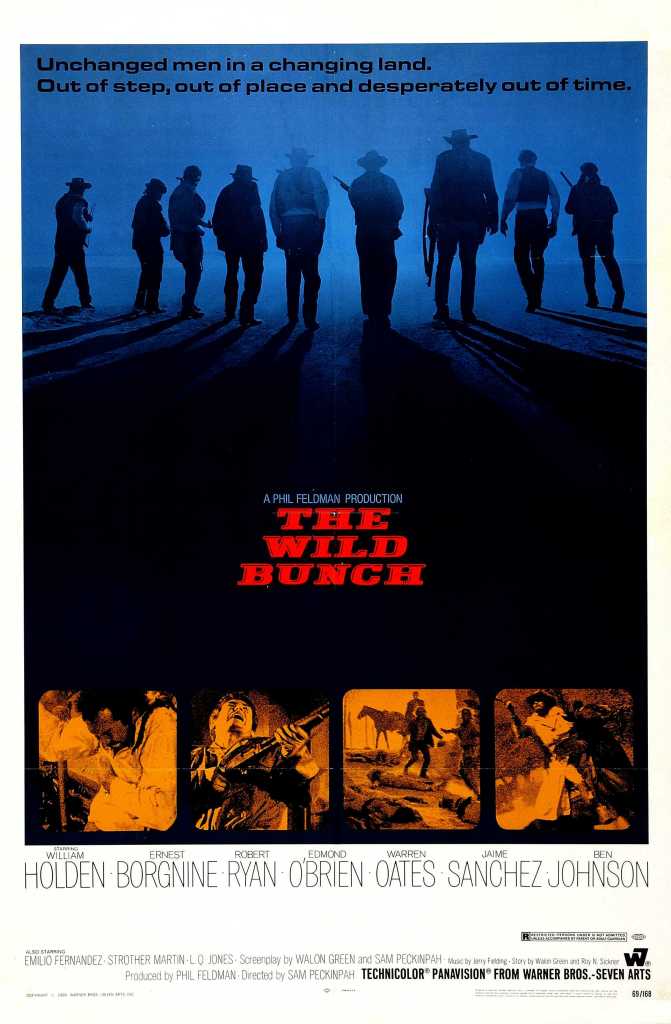

Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 film The Wild Bunch proved to be a massive success for Warner Brothers. Released two years after Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967) which pushed the boundary for violence portrayed on the silver screen, and released the same year as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) which changed the landscape of American independent cinema, Peckinpah’s film is historically considered the major turning point for the Western film. Arguably the first modern Western, Peckinpah had directed this film with Vietnam in mind. By that point, the Tet Offensive catapulted American involvement in the conflict to what we now recognize, and war footage was being televised to every American home, every night just in time for dinner.

Peckinpah’s films are often criticized for their hyperviolence, often romanticized with this signature editing technique of splicing together slo-mo footage from one perspective with real time footage from a separate perspective. However, Peckinpah was concerned with the desensitization towards violence with the war footage being televised, that he had hoped his films would be so violent that it would purge the violent nature of the audience that watched it. But what’s significant with the history of the production of The Wild Bunch was that within the same month of release, you would have seen multiple wildly different versions of the film. So with that said, this week is going to be a lot heavier on the history of the making of the film as well as how it fits with my theory of Westerns as a form rather than a genre.

To start, this film was a massive return to form for Peckinpah. While he had made a handful of films in the early sixties, namely The Deadly Companions (1961), Ride the High Country (1962) and Major Dundee (1965), Peckinpah was pushed into television for all those years between, so his employment of director on The Wild Bunch was a massive career move for him. He received the script and submitted multiple drafts of it, editing the screenplay as the cast got finalized because Peckinpah always believed that his characters should be written to the actors playing them. So the film got made, and it’s interesting to note that Paul Seydor in his book, Peckinpah: The Western Films, acknowledges that the studio and producer Phil Feldman advocated for more violence in the film than what Peckinpah initially gave them (p. 79).

But oftentimes, Peckinpah returns to the motif of the kids with the ants and scorpions to undercut the portrayal of violence in his films. At the most grotesque and tragic, there are always children around watching in glee. This acts as a conduit for the audience, the notion that these kids don’t know any better and are often witness to violence unwillingly but simply don’t know what to make of it. However, Peckinpah acknowledges that the audience should know better and challenges us with his signature editing technique I had mentioned before. This Brechtian technique of his will often pull us out of the film and accept that the disjointed nature of what we are watching is no longer reality, but is still a perfect marriage with the aggressive real time footage of a man falling off a horse for example, and the beautiful and meditative slo-mo footage of the same action from a different perspective. The violence we see is at the same time horrific and aesthetic, and that challenges us to question why we are perceiving it in that way.

The film was released in early July in a 143 minute cut. However, in late July the same film would be seen in a 135 minute cut. The story goes that Peckinpah, having wrapped on this film and a second film back to back, took a much needed vacation and couldn’t be reached. However, producer Phil Feldman managed to get ahold of him and proposed an experiment in removing or re editing some of the flashback sequences, but only for a couple of theaters. Peckinpah agreed to it as an experiment and a couple of theaters, but multiple prints got pulled from hundreds of theaters and re edited with four whole scenes removed. Allegedly, the cuts were made on account of theater owners, who believed that removing 8-10 minutes from the film would open up space for a second screening in the day. However, many theaters didn’t take advantage of that extra time to show a second screening, and instead used that extra time to sell more refreshments. One theater used that time to screen Tom & Jerry cartoons (Seydor p.83). So with that, the 143 minute cut of the film was largely unavailable until more recent years, but this whole episode serves as an indictment on a lack of artistic integrity and a clear example of the American film industry’s concern with profit over artistry. But I digress.

Returning to the film, Peckinpah also wanted to steer away from the heroics of what audiences would have been familiar with in Westerns, and instead wanted to reach a point of reality. The reality of what type of man would have flourished in the lawlessness of the Wild West, the type of man who would have been making the laws, and the type of man that would have been affected the most by the modernization of the country by the early 1900s. With railroads and fences and cities to keep them confined, the thesis of this film could consider the iconic line from Pike Bishop, wherein he says, “We’ve got to start thinking beyond our guns. Those days are closing fast.” Another major motif throughout the film is the concept of word vs, deed. How Pike will proselytize to the Bunch the value of keeping your word, “When you side with a man, you stay with him. If you don’t then you’re some kind of animal.” However, on numerous occasions Pike will contradict this statement. Additionally, Peckinpah chooses to return to the origins of storytelling and mythmaking as the narrative treatment of the characters will oftentimes reflect Homerian epics with The Iliad being a specific example. This, I will elaborate on later but these are the major themes that undercut the events of the film.

So with the ambush having cut the Bunch’s numbers and half, and them making out with nothing more than iron washers, they flee to Mexico which in 1913 was in the midst of a revolutionary war between Pancho Villa and General Huerta who at this point would have also been President of Mexico. The Bunch make their way to a small village that was Angel’s birthplace, only to find out that Huerta’s forces led by a general named Mapache went through the village and killed Angel’s father and stole his woman. However, Angel on a revenge trip, the Bunch decide to aid the villagers and thus the village accepts the Bunch as a sort of folk hero group. They drink and dance and celebrate, the Bunch taking some needed time off, and it is here where Pike and Dutch watch as the Bunch celebrate, with Dutch remarking that “We all dream of being a child again. Even the worst of us.”

The next day the gang set off, but the sorrowful music and the dour attitude of everyone makes the departure of the Bunch feel like a sort of funeral procession. Angel’s mom comes to bless him on his journey, and keeping Vietnam in mind, this scene plays much like the sending off of newly drafted troops. They’re heading to their doom, and everyone knows. Is their departure as heroic as we think it is? Of course, the Bunch could be considered bad men put in a position to do some good, while American boys drafted to fight in Vietnam are good, innocent children put in a position to fight a pointless war. So there’s differences however the similarity comes to mind and this scene feels like a major turning point for the tone of the film as well as the question of the Bunch’s mortality.

Comparisons between the conflict in Mexico brings to mind the everlasting conflict of the indigenous North Americans and the White American settlers. Here in Mexico, we’re following the conflict between the indigenous of Mexico and the militarized government that senselessly takes their land. Naturally it begs the question of whether Peckinpah was trying to use an easily sympathetic perspective in a different context with the Mexican villagers to draw comparisons between what the Mexican government did to what the American government did to the tribes. When we meet Mapache, he’s concerned with technology and its wartime use, while the rural villagers simply want to live their lives.

With that said, the Bunch rides in and meets Mapache in his compound. Mapache’s introduction is incredibly violent, with a fanfare preceding his driving into the compound in a cherry red motor carriage. Like War on top of his Red Horse, the introduction of the car is also brought about with incredibly staccato editing. We barely get a good look at it while it’s in motion, because it’s almost too incredible to be true. Plus, the cherry red juxtaposed intensely with the earthen tones of the film make the car seem otherworldly. There’s nothing else in the film that’s colored this vibrantly and it really stands out. It’s also questionable if the Bunch themselves have ever seen a car, so for them a top horse-back to all of a sudden be introduced with this advanced technology invokes the likes of Theseus meeting the Minotaur. Before the Bunch officially meet Mapache, Angel spots his betrothed Teresa. They have a quick exchange that’s exclusively in Spanish, but with a small knowledge of the language as well as Peckinpah’s masterful use of the visual language, we can tell that Teresa is much happier away from the village and in Mapache’s arms.

Angel watches as Teresa runs to Mapache and embraces him, kissing and licking his ear ensuring that Angel watches. He violently reacts and shoots Teresa and this is what introduces Mapache to the Bunch. Dutch explains the situation, and Mapache finds humor in Teresa betrothed leaving him and him having that reaction, so he invites the Bunch to drink with him. He provides food, drink, and female companionship to the Bunch while he, a German advisor, Dutch and Pike go over a plan to steal a shipment of U.S. Army weaponry for Mapache’s use. Throughout this dinner, a funeral procession carries Teresa’s body past the tables which brings me to my next point.

It’s reasonable to believe that the women in this film have little to no autonomy. This has always been a major criticism of this film in particular, but that’s for a reason. Throughout the film, we always see women running to protect their children during a gunfight, women used as literal meat shields, and women the victims of male anger and aggression. This invokes this notion of identifying the protective nature of women, and how often they’re used as defensive barriers for male aggression, whether that be literal violence or emotional outbursts. Women protect those they love, and are often chewed up and spit out by the male led society. While I won’t pretend that Peckinpah was a feminist, the decision to have this be seen is clearly conscious as a critique of the motives that drive men to action. Which also brings me to the flashbacks seen throughout the film.

There are three notable flashbacks that give context and history for Pike, his relationship to Thornton and how Pike ultimately got shot in the leg because of a woman he loved. While this one in particular was the last flashback we see, it was also one of the ones that got cut in the shorter version of the film which is horrifically criminal. In this flashback, it is revealed that Pike had fallen in love with a married woman whose husband had abandoned her. Pike, being a “man of his word” as he claims to be, is questioned by the woman as he was supposed to be there for her two days prior. He made that promise and broke it and when she questioned it, he brushed the question away. Another quote of Pike’s is that “it’s my business to be sure” so he asks the woman if her husband truly won’t come back. She says she’s sure, but to no one’s surprise her husband did in fact return. He shot her dead and shot Pike in the leg and ran off. Pike dreams of catching up to that man, because he truly loved this woman. But as I have mentioned before, she was caught in the middle of two men’s ire and paid the price for their actions.

Another of the important flashbacks shows Pike’s relationship with Thornton. We witnessed this flashback in an earlier scene of the film, cutting in and out of the flashback to close-ups of both Pike and Thornton in separate locations, thus connecting them through this shared memory. The flashbacks are introduced with the wavering effects that feels so cliche especially now, since it is often used as satire. However, its use in this film invokes the image of water, and that no matter at what point in their lives they are, these memories sit just under the surface for Pike and Thornton. Nevertheless, this flashback in particular is about a robbery that Pike and Thornton planned on making together. Thornton was on guard, but Pike was enjoying a bath and some liquor with women and was so sure that he and Thornton would be safe. His business is being sure after all. But nonetheless, Harrigan (the man who owns the railroad company they robbed and the same one robbed by the Bunch in the beginning of the film) leads Pinkerton agents and shoots Thornton. Pike manages to get up and run off, effectively abandoning his partner. Additionally, it’s noted earlier that C.L., an unpredictable and mentally unstable member of the Bunch present in San Rafael, was Old Man Sykes grandson. But due to his unpredictability, Pike made an effort to leave C.L. behind. While Sykes never learns of PIke’s true intentions, it’s another moment of not living up to his own standards to weigh heavy on Pike’s conscience. He’s constantly fighting the uphill battle of rectifying his past behaviors with himself, but can’t bring himself to forgive. In Seydor’s book, he words it as a “Disparity between word and deed that eats at him throughout the film” (Seydor p.89).

Important to note as well, Thornton has talked about Pike to his gang of hunters, referring to him as being “the best, never got caught.” While Pike has certainly never been caught, what we see of him contradicts this statement of him being the best as we’ve seen numerous times Pike making major mistakes that cost other men’s lives. Pike knows this too, and swears by himself that he just wants one last big score to prove to himself that he’s capable. Which brings us to the train robbery.

For once, Pike’s plan goes without a hitch. Thornton is sure that Pike would target the train, so he’s there with his gang as well as a battalion of “green recruits” from the Army. Close ups of these boys show that a majority of them barely seem past adolescence. Inexperienced and uneducated much to Thornton’s chagrin. Regardless, the Bunch mount and rob the locomotive, and unhitch it and the car carrying the weapons from the passenger compartments of the rest of the train. It’s not until the locomotive is well on its way that Thornton looks out the window and sees the successful robbery. He rallies his gang and they ride off after the Bunch, while the Army soldiers sit in the car unaware or simply asleep.

Previously, Angel had asked Pike to take a crate of weapons to deliver to his village. He gives up his share of the money Mapache is paying them in exchange for a case of rifles that he believes will help his village fight back against Mapache and Huerta’s forces. So when the Bunch successfully make off with the weapons, they’re caught by surprise by the indigenous Mexicans who have come to collect the weapons. “They’re puro Indio” Angel says “they own these mountains.”

But ever the cautious one, Pike leads the Bunch back towards Agua Verde where they will deliver the weapons to Mapache, but are intercepted by one of Mapache’s men who plan on taking the weapons without paying. However, Pike has rigged the wagon with dynamite, and threatens to blow it up at any sign of trouble. Therefore, Pike hides out each of the crates at different locations, and sends his men one by one to deliver the location of the weapons and to return with the money. If the men don’t return, the weapons are destroyed.

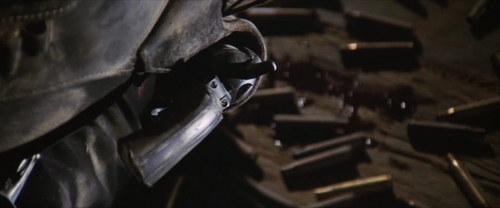

With my mention of the car before, it’s known that Peckinpah has a deep hatred of technology, claiming that the camera isn’t technological but more so a divine gift. But the presence of the car is ominous, and within this cache of weapons, the Bunch finds a machine gun. Lyle asks Pike “do you know how to use this thing?” to which Pike remarks that if he doesn’t he’ll find out. Once again, the introduction of a new piece of technology that symbolizes the death of the Old West that we’re familiar with. At any point in the film that the machine gun is used, it seems divine. It seems incapable of human use. Mapache finds out that the weapons shipment included the machine gun and Pike remarks “our deal was for 16 cases of rifles and ammo, not a machine gun. That is my gift to the general.” Mapache proceeds to wield it, with the German yelling down that he must put it on a tripod, so of course when Mapache fires the gun it swings out of control. In a very slapstick display, the entire population of Agua Verde ducks undercover as Mapache spins around firing off in every direction. This is technology that can’t be wielded by a man, the use of an additional piece of technology is necessary.

But this exchange comes to an end when Dutch and Angel come to deliver the final location of the weapons. Mapache remarks that there were supposed to be 16 cases, but there’s one missing. He immediately recognizes that Angel stole them, to which Dutch gives him in. If Mapache were to know that the Bunch allowed Angel to steal a case of weapons, they would all be hunted down and killed. But Angel takes the fall, and Dutch is forced to abandon one of his men. Something against his code, but something necessary for his survival.

Dutch returns without Angel, and Old Man Sykes goes out to retrieve the horses hitched to the wagon carrying the weapons. In this moment, Pike is put in a position where he has to confront his historical abandonment of his men, his inability to live up to his own standards. Either go back to rescue Angel or abandon his men once more. At this moment, Thornton and his gang show up as Sykes returns with the horses. One of the hunters manages to shoot Sykes in the leg while the rest of the Bunch ride off. Thornton leaves one of his men to find Sykes, telling him “once the buzzards come for the body, just follow them.”

So Pike, Dutch, Lyle and Tector return to Agua Verde and Pike offers his half of his earnings to buy back Angel. Angel is now being dragged behind the cherry red car, with the children of the village gleefully throwing rocks, burning his body with sparklers, and jumping on him and riding him like a horse. But he’s still alive. Mapache refuses to give up Angel, but promises the Bunch free drink and women at the bordello, and they have no choice but to accept.

The next day, Pike rallies Dutch, Lyle and Tector. They know what they’re meant to do, so when Pike says “let’s go,” Lyle remarks “why not?” A quote from Seydor’s book puts this moment of reinvigorated motivation as Pike’s acknowledgement that if they “walk away, then your life’s a fraud. Stay and fight, then you’re life’s over” (Seydor p.98). At this point, Pike will no longer abandon his men, even if he knows he won’t come out the other side.

Much like the first shot of the film, the Bunch go into the metaphorical cage of Agua Verde as scorpions, surrounded by the red ants of Mapache’s men. They demand Angel one last time, to which Mapache responds by cutting his throat. Pike quickly draws his gun and shoots down Mapache, ending the Red Rider of the Apocalypse and now being left with his army of men. There’s a moment of silence, the four men looking at each other in anticipation. The silence is cut with laughter from Dutch, and then the Gorch brothers as they accept their fate. This is it, but they won’t go down without a fight. Much like the epic heroes of Homer, Pike aims at the German and shoots him down, igniting the final gunfight.

We notice as the four men get shot numerous times, but they rush the town to get to where the machine gun is mounted. Tector is taken out, and Lyle wields the machine gun. He gets kicked back by the divine recoil as well as the gunshots tearing through his torso, but stays fighting until his very last breath. In a last act of heroics, Pike mounts the machine gun and ultimately falls, as Dutch watches and dies himself. The final image of this carnage is a mountain of bodies, with Pike’s corpse at the peak. Hand still on the machine gun, his head hung down and the gun pointed up like some sort of painting depicting a historically significant event. This last action cements their lineage as folk heroes as well as liberators to the people of the village.

A ways off, Thornton and his gang hear the gunfight but stay back. Much like the buzzards mentioned before, they descend upon the wreckage to loot the bodies of the deceased and to claim their bounty of the Wild Bunch. Thornton finds Pike’s body, and takes the revolver from his holster. He laments this loss. For finally, he is reunited with his long lost brother. The bounty hunters take off with their winnings (not making it far before the indigenous defend the bodies of their heroes) and Thornton sits down and just waits outside the gates to Agua Verde. Pike is gone, he has nothing else to live for, but it is then when Old Man Sykes returns and asks Thornton to join him once again.

The closing credits play over images of the Bunch, much like the danse macabre at the end of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), but also with the fades to monochrome over the images of the men, it invokes lithograph images of heroes of days past. Seydor refers to this in saying “Peckinpah’s purpose is a retelling of history not as documentary but as metaphor angled toward recovering a mythology” (Seydor p.107). The ending credits leave us in this state of introspection thinking about the death of the culture behind these kinds of men, but also in the idea of bad men being driven to do something great. There was no way men like that would be able to continue living in the modern 20th century, so their ultimate sacrifice was to place themselves as the figures of heroic mythology.

Which brings me to connecting this with my theory. So call the Western a genre and make the connections between a film like this or The Searchers (1956) and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) is redundant. We have the revision of what we perceive as mythological heroes vs. the creation of one. These ideas work wonderfully in their respective films because yes, although The Searchers came out 13 years before, it feels like a response to a film like The Wild Bunch. It’s easy to idolize a person because of their great stature and great deeds, but their history is ever present so at what point should we stop and question whether the Bunch have earned their spot as heroes, or were just in the right place at the right time? Nevertheless, it’s clear that the structure and intent of these kinds of films differ so varyingly that the only easy connection is the time period, the locations and the costumes. Seydor in his book describes Westerns and Peckinpah’s relationship to them as “a whole language of myth, symbol, and metaphor waiting to be exploited” (Seydor p.103). Peckinpah down to his bones was a storyteller of the ilk of Homer and Shakespeare. They were mainly concerned with telling a compelling story in the language that they could express excellently and became legends in their own rights because of that.

My final point brings me to question if Westerns are simply a form, how could The Wild Bunch be identified alongside the likes of The Searchers or The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly through their similarities and differences? There’s this talk of it being an “anti-Western”, that it’s revising and correcting the faults of the form. For this, I would like to finish with one last quote from Seydor’s book, “If The Wild Bunch is to be seen as an anti-western, then it is not seen at all. The whole point of its conflicting perspectives…is not to “expose” the western, much less to erode the basis of its heroic virtues which Peckinpah carries all the way back to their first appearance in the epic tradition” (Seydor p.136)

The Wild Bunch was watched on the Warner Brothers blu-ray release

REFERENCES:

Seydor, Paul. Peckinpah: The Western Films. University of Illinois, 1980.