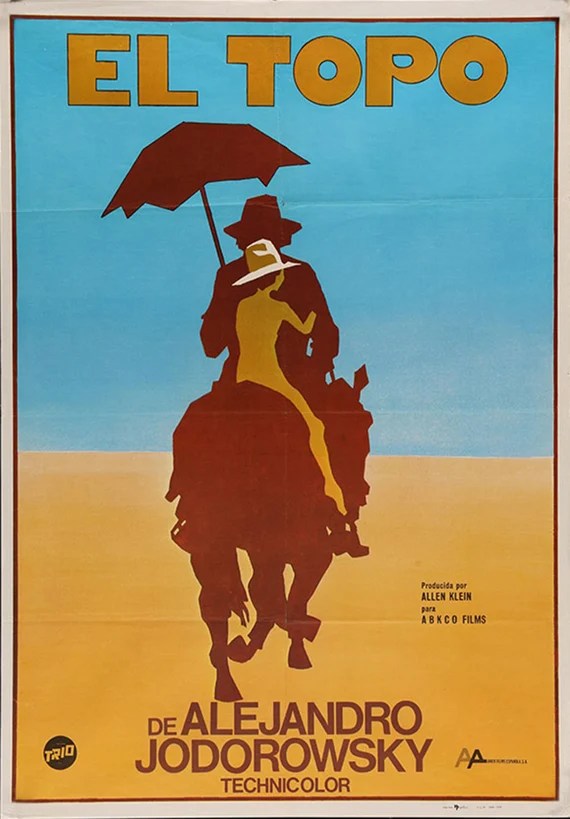

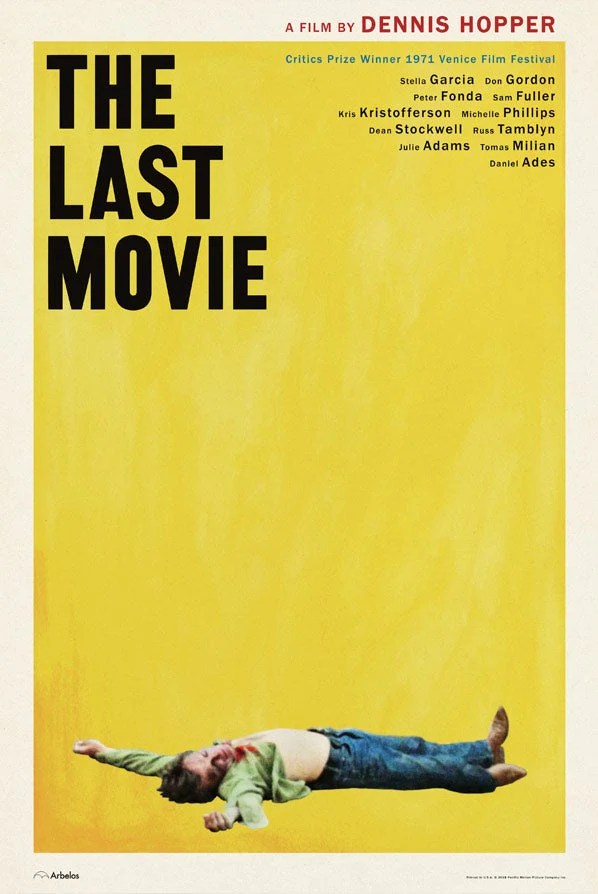

El Topo and The Last Movie

Written by Mario Martin 8/21/2024

With Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) being the film that changed the landscape for westerns to come, I felt that it was logical to follow up its modernist ideology of man vs. heroics with two acid westerns with varying postmodern ideologies. For this week I take a look at Alejandro Jodorowsky’s seminal El Topo (1970) and Dennis Hopper’s long unavailable formalist experiment The Last Movie (1971). Convenient, considering these are two acid westerns that I consider fundamental to who I am as a person and an artist, as well as the fact that the first filmmaker is responsible for the way the second film turned out.

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a Chilean-French filmmaker who is the co-founder of the Panic movement of avant-garde theater, as well as the filmmaker behind the controversial Fando y Lis (1968), The Holy Mountain (1973), and a never realized adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune. An avante-garde filmmaker and mystic, Jodorowsky’s films are often filled with surrealist imagery motivated by the teachings of Freud and Jung, as well as imagery related to occultism, sacred geometry, the Marseille Tarot and religious iconography. The landscape of his film El Topo is a nowhere wasteland, a psychological void with no semblance to any place in reality or connection to any part of reality. Out of space and out of time, the desert in El Topo allows Jodorowsky to explore his effervescent explorations of psychological theories and religious dogma. This film is considered the first of the sub-type of “Acid Westerns” and these elements serve to develop such an idea.

As for Dennis Hopper’s enigmatic follow up to his trend setting 1969 counter-cultural hit Easy Rider, his film The Last Movie is set in contemporary Chinchero, Peru. Set on and within the aftermath of a Western film set, Hopper’s film explores the human desire for filmmaking as well as the blurred lines between the fiction and the truth in art. If El Topo’s postmodern ideology is man vs. dogmatic faith, The Last Movie’s is man vs. the filmmaking form itself.

Narratively, El Topo remains relatively spartan. If I were to sum up the narrative in its simplicity, it’s about a man who conquers four master gunmen, gets betrayed and exacts his revenge on his betrayers whilst liberating a community of disenfranchised people. As straightforward as that may be, Jodorowsky’s use of sacred imagery within this film paints an exploration of “the ultimate truth” or “absolute enlightenment” as well as the obsessive pursuit of such.

The film opens with the titular character and his naked sun arriving by horseback at a location that will be used by our protagonist to teach his son a lesson in maturity. “You are six years old, you are a man now. You must bury your first toy and a picture of your mother,” he says to the child. The liberation of material possessions on their part as well as a lack of obvious clarity and purpose introduces us to this film and its ideals. With the son being naked, he is supposed to be naive and free. El Topo himself is a gunman clad in black. Historically, the black gunman is perceived as morally reprehensible. It’s reasonable to be suspicious of this man and his intentions, for we learn that he himself is on a journey of enlightenment.

We then cut to the opening credits with a voiceover from Jodorowsky himself (who also plays the titular character) describing “el topo” or the mole, “who burrows searching for the sun. When he finds the sun he is blinded.” Presupposing the plot of the film itself, it poses this notion that the obsessive search for enlightenment can be just as if not more blinding than the lack of enlightenment itself. It’s a matter of the journey taken to get there.

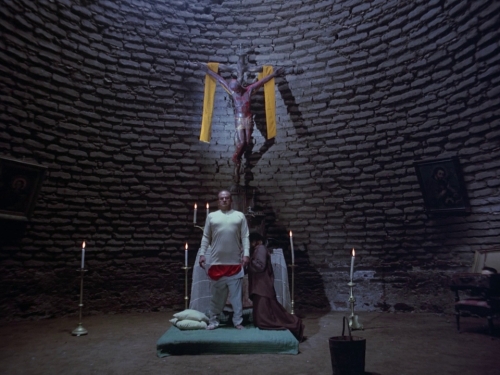

This notion is revealed when El Topo and his son (aptly named “Hijo”) happen upon the desolation of a town where the street literally runs red with the blood of its deceased inhabitants. Immediately searching for the perpetrators of such an atrocity, El Topo and his son journey to an out of the way Franciscan chapel under the crooked command of The Colonel. A man in make-up and satin underwear, he’s the spitting image of Victoriano Huerta, general and ex-president of Mexico during the conflict between the imperialists and the villagers under Pancho Villa. We first meet The Colonel’s gang as they molest, assault and harass the monks of the chapel, coercing them to dance and kiss and embrace.

But El Topo comes to this commune and immediately eradicates one of the gang members in a violent fashion. For a film with such a concern for spiritual enlightenment, the violence and gore within this film feels incredibly striking. For the image of such a sacred man to be committing acts of violence almost as aggressive as his opponent feels like an ever poignant point about the ways in which a search for enlightenment can become so easily bastardized. But this act of violence against the gang member hardly compares to what we saw in the village, albeit the camera lingers on him as he bloodily stumbles his way through the chapel graveyard.

But we come to The Colonel, who abuses those around him. The one woman in this commune is his plaything, his gang is forbidden to touch her because she is hers, and he also abuses his inferiors. But when it comes to blows with El Topo, the lone gunman takes joy in the emasculation of The Colonel by shooting his toupee off, as well as the buckles fastening his clothes. When confronting his deathbed, The Colonel asks the titular character, “who are you to judge me? I’m God.” With this first proclamation of a presupposed divinity, The Colonel introduces us to the first instance of obsessive pursuit of enlightenment. However, this man was not enlightened. He didn’t pursue an inner truth, and instead abused his power. As such, El Topo castrates the man which proves to be his death.

The monks’ retribution for the surviving gang members is to cover them in sheets and gun them down, with El Topo ultimately abandoning his son with the monks and taking the woman with him. Immediately, we find El Topo and the woman by a lakeside. He meditatively plays his flute while she tries to drink the lake water, but finds that it’s too bitter to be potable. With a branch, El Topo stirs the water and tells a story of Moses and his followers finding a source of water that was too bitter to drink, so Moses used the power of God to bless the waters to make them drinkable. He says they called the water “mara” so he christened the woman with that name. It’s interesting to note, that while El Topo serves as a Christ image within the film, Mara is the name of the demon in the Buddhist faith that tempted Siddartha Gautama (the one we know as The Buddha) on his journey of enlightenment. Much like Lucifer with his trials against Christ, the naming of this woman presupposes her role within his own journey of enlightenment.

But from this point, we get a montage of El Topo performing various miracles. He has Mara stand with her legs apart, and digs in her shadow to find eggs to eat. He finds a phallic rock out in the desert, and shoots the tip to release a geyser of water. But when Mara attempts the same actions, they’re to no avail. It’s not until El Topo slaps and rapes her that she is able to perform these miracles. With his nonchalant sharing and teaching of these miraculous acts, it brings to question El Topo’s spiritual integrity. With Mara’s rape, it brings to question the forced dogma of certain faiths, and the victimless narrative that’s shared within various scripture. The history of various religions are filled with bloody conflict, with them either as the perpetrators or victims, especially within the context of the Judeo-Christian faith. With El Topo being a pre-enlightened image of Jesus Christ, his actions seem to be a projection of Jodorowsky’s image of Christianity and its actions. But despite that fact, Mara still accepts him but weaponizes her love and affection by commanding him to confront four master gunmen. These four gunmen we soon come to meet are images of various faiths and beliefs that challenge El Topo’s journey of enlightenment.

The first gunman we meet seems to be a loose resemblance of Hinduism. His companions are a paraplegic duo, one without arms who carries on his back one without legs. In tandem they allow El Topo to visit their master, the first gunman. Through meditation, he has hardened his skin so that a gun shot in his shoulder produces the blood that you would expect out of a paper cut. He preaches his embrace of the literal and metaphorical darkness to El Topo, with this gunman living within the darkened chambers of a tower. However, when the time comes for El Topo to confront the master in a duel, he succeeds through trickery. At Mara’s behest, a trap is set so that the first gunman falls into a pitfall as El Topo shoots him in the head. Through his deceit and trickery, El Top eradicates the first gunman’s attempts to educate and enlighten the lone gunman in his ways. Circumventing the teachings and journey, El Topo grieves his use of “the easy way out” as Mara takes it into her hands to take out the paraplegic duo. It is here where a mysterious woman in black who speaks in a man’s voice comes to guide them to the other three master gunmen.

Happening upon the second gunman, El Topo finds a man and his wife. The wife sits at a table with a Tarot deck in front of her, while the gunman explains to El Topo how he has hardened his hands by making copper objects, but further strengthened himself by making delicate objects out of sticks. “I am so strong, I can hold this object without breaking it” he says as he hands it to El Topo who immediately crumples the item. Through this training, it is seen that the gunman is a much faster draw than our protagonist could ever hope to be. As with the first master, this one attempts to teach El Topo the path to enlightenment but he once again takes the easy way out through tricks and deceit.

El Topo arrives at the third gunman, who resides within a corral of white rabbits who are slowly dying out as our protagonist comes closer. The gunman acknowledges that sentiment and it begs the question of the purity of these white rabbits (symbolically being a guiding force as was the case in Alice in Wonderland) being tarnished by the alienated search for enlightenment of our protagonist. By this point, it’s clear that he isn’t putting in the work to reach this enlightened state he pursues and it’s come to cloud his judgment. With this gunman, he claims he only needs one shot, as he’s accurate enough to shoot El Topo in the heart on the first try. Sure enough, he does. El Topo falls but slowly gets up laughing. A copper plate he had taken from the second gunman had stopped the bullet so he tricked the third master and survived. El Topo guns him down and we see as every last rabbit in this corral has died. El Topo buries the man under his dead rabbits and moves on to the final gunman.

The anti-catharsis of El Topo’s journey comes to a head when he confronts the final gunman, a lone bearded man with no possessions besides a butterfly net. He laughs at El Topo’s declaration of a duel, as this master no longer has his gun. He then pulls the destroyed and rusted pistol from beneath his feet and claims that he traded his gun for his net. His rejection of the pistol being his state of ultimate enlightenment. This angers El Topo who fires, but the man catches the bullet with his net and whips it back to him. Acknowledging the futility of his journey and his lack of gain, El Topo falls to the ground in grief. The final master acknowledges his wasted journey and proceeds to shoot himself. The final step of his enlightenment journey is now fully out of reach. The end is so lacking in any catharsis for the audience or for the protagonist, we too feel that this whole journey was an absolute waste.

El Topo’s return to Mara and The Woman In Black shows us the sites of his “accomplishments” as they have become desecrated. The third gunman buried under his rabbits ignites in flames, the second gunman and his wife are found buried under the fragile structures the gunman was known to make, and the first gunman being coated in honey and bees. However, his lack of involvement in the death of the final gunman may have been his solace because the violence that the self-righteous man had enacted was pointless. It did him nor anyone else involved any good, and was simply done in the name of Mara’s conditional love.

It is here where Mara and The Woman betray El Topo, joyfully gunning him down as he crosses the bridge to them and running away together. The bullets hit El Topo in his hands, feet and lung in the image of Christ’s stigmata. It’s reasonable to believe that may be his spiritual repentance. He strayed too far from his goal and his personal God and this is how he must pay. However, this could also be seen as the true first stage to his quest for enlightenment, for following this betrayal we see as the black gunman has turned white over years of meditation within a cave.

A title card brings us several years into the future where we see that El Topo’s hair has grown white and he wears a white gown. Spending these years meditating on the teachings of the master gunmen, El Topo has finally reached this ultimate enlightenment that he has pursued by his own work and his own volition. It is here where he must put it to practice, as he shares the cave with a community of differently abled people who can’t reach the outside due to a rock slide that has cut them off from the rest of the world that has alienated them. El Topo takes a woman as his wife and leads her outside to the nearby town where they perform degrading shows to the laughing townspeople so that they can save money for dynamite to free the rest of the people in the cave.

Here we find that Mara and The Woman have grown old and fat over the riches that they manipulated from their people and from the church they run. The banner is painted with the image of “The All Seeing Eye” and church service is awfully reminiscent of Protestantism with all of its hypocrisy. It is also here where we see Hijo once again, who has come to the church to practice his faith and is outraged at the state in which it is run. He reunites with his father. And promises to kill him to exact his revenge for abandoning him as a child, but will help him lead the people out of the cave.

This journey comes to an end when El Topo is finally able to lead the people from their cave, but as each of them are los topos in their own right, the sight of the sun blinds them and the liberation from their cave leads them straight into their deaths. The townspeople gun down all of the people from the cave, and El Topo resorts to violence once again to gun down the townspeople in return. However, we have continuously seen that violence is not the path to enlightenment for El Topo, and this final action has signified his straying away from his enlightened state. As such, El Topo resorts to self-immolation in the likeness of the Vietnamese monk Thich Quang Duc who performed the action as a protest against the treatment of the Vietnamese Buddhists by the hand of the Roman Catholics. But this sacrifice proves to be the last miracle El Topo will ever commit as the film ends and we see Hijo, El Topo’s widow and his newborn son ride away from the desolation of the village, a similar desolation to the one we saw in the beginning of the film. The ultimate thesis of this film being that with El Topo’s quest for enlightenment, the true solution was a rejection of bias, an acceptance of the work needed towards introspection, and the embrace of selfless actions to achieve a state of enlightenment. It is not a journey of accepting tithes, performative miracles and the abuse of others to achieve your goals.

In terms of how this film fits within the general form of a Western, it’s certainly one to break conventions. Could anyone argue that this isn’t a Western? Maybe, but with the conventions that I have mentioned previously, this film seems to avoid them. There’s no sense of manifest destiny, the American Civil War may not have even happened within the context of this film, the black clad gunman has a sort of redemption arc, there’s a number of things in place that both don’t support this film as being a Western, while stating that it can only be a Western. This is what Jodorowsky introduced with his trendsetting Acid Western, with the embrace of Eastern philosophies and a more metaphorical journey than a literal one.

When considering Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, it’s very interesting that the film opens with Hopper on horseback, riding across the emerald plains of Peru, with the vibrant blue sky and snow capped mountains behind him. An image so synonymous with a Western, this is a film that crosses a lot more boundaries. Less so concerned with the metaphorical journey or quest for enlightenment, this film approaches the metatextual journey of deconstructing the form and human necessity for storytelling. As such I watched The American Dreamer (1971) a companion documentary that follows Hopper as he approaches post-production on his film.

It’s foolish to try to summarize the film’s narrative in the way that I’ve been doing so I will say this: the film follows a horse wrangler named Kansas on the film set of a Sam Fuller production of Billy the Kid. In the aftermath of an actual death on set, Kansas stays in Peru where the locals have taken to the abandoned sets to reenact the violence of the film that was made, but without the guise of filmmaking and is instead real violence. There’s some plot to dig for gold in the mountains that turn fruitless, but Kansas is perceived by the locals as the authoritative figure on Western filmmaking.

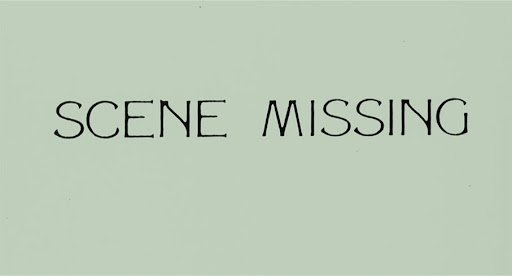

But the film contains so many metafictional observations that taking the film at face value is simply the wrong way to approach the film. Immediately apparent is the film is edited in a chaotically nonlinear fashion. From the opening shot we cut to Dennis Hopper as Kansas, bloodied and beaten, limping through the crowd at a impromptu beauty pageant to cast the female lead in this communally imagined film. From here, we’re on the set of Billy the Kid where we see several boom mics, slates, the backsides of flats and the inner workings of a film set within the film itself. Linearly, we watched the second to last scene cutting to arguably one of the first. This nonlinear editing serves multiple purposes in what Hopper was approaching with this film.

In the documentary, it’s made glaringly obvious that Hopper was in a perpetual pursuit of some sort of human truth. He often improvised with actors, waited until after a take to actually start rolling the camera, and desired to make it obvious that The Last Movie itself was in fact just a movie. With this pursuit of an artistic human truth, the presence of the nonlinear editing and Brechtian observations of a film set put the audience in a position to take the film at a distance. To not get entirely emotionally invested or empathetic towards the film’s players, but to step back and question the objectivity or subjectivity of the story that we are being told. We question the form and nature of storytelling, as well as acknowledge that the lack of a coherent narrative is awfully alienating. We acknowledge that we as humans need our stories and tales to find nourishment within our lives, and being presented a story that doesn’t make sense is one of the most criminal things to the general public in art. However, the confusion also allows the audience to get further invested and unlock their own subjective truths within the story that is told. The art of surrealism works because there’s no objective way to take it. The creation of that work of art is personal to the artist, and we’re allowed to personalize said work of art’s meaning to make sense within our own lives.

On that note, I also felt that the nonlinear editing signified the subjective nature of the human experience. Our memory, collective or individual, isn’t perfect. Recalling past events, we tend to leave details out or emphasize others for the memory to make the most sense, to have the most impact on how we’re remembering it. Our memory itself isn’t linear, and storytelling has always been a conduit for memory. With the invention of cinema, we now added an extra element for our collective memory. In theater, we maintain one objective perspective as the audience, but cinema allows us room for subjectivity with the use of various framing devices and editing techniques. Hopper with The Last Movie forces us as the audience to consider all of these elements to make our own sense out of the incoherently presented film.

Hopper in the documentary mentioned the camera as being this “outside thing” or an observer, the element itself that allows our own subjective interpretation of art. I mentioned in my post on The Wild Bunch that Peckinpah believed the camera to be a divine being in its own right. It wasn’t created, but simply gifted to us by the heavens. Within The Last Movie, we see the Peruvian locals parade a replica of a movie camera fashioned out of sticks, through the streets as if it were a statue depicting a saint or divine being of faith. The construction of the sets has become their chapels, and the actions on set have become their gospel. Cinema has become a religion for the locals of Chinchero, Peru and the camera is their God. However, does this development of a faith bear any difference towards the development of an established religion such as Islam or Christianity? They all originated as gospel, stories shared with us with a moral interest, scripture to proselytize our ideals to those yet initiated. Admittedly, that is exactly what I am doing with this blog. I’m singing my praises of the cinematic form and sharing with others who may or may not be initiated with this religion I follow. Humans need storytelling. Me attending the theater every Friday is no different than attending Mass on Sundays.

Dennis Hopper with his film makes an effort to continuously cross the boundary between the presented “reality” of the film and what the film itself considers to be fiction. We never know whether we are watching an event presented as The Last Movie or as an event on the set of Billy the Kid. Hopper continuously crosses this line throughout the film and further puts into question the “reality” of the narrative. Kansas himself is hardly the unreliable narrator, the film itself is totally unreliable at giving any sort of information to the audience directly. Much like El Topo within Jodorowksy’s film, we as the audience have to work towards the enlightenment and questions provided to us by Hopper within his work of art.

I alluded to this point before, but Jodorowsky is largely responsible for the shape in which The Last Movie was presented. Hopper had presented a pretty traditionally edited cut of his film, but the story goes that Jodorowsky had mocked Hopper and told him to “break new ground” with his film. Spurred by this sentiment shared by Jean Luc Godard, “a story must have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

Interestingly, the metafiction of the film transcends its observation of the storytelling form, and becomes prophetic in certain ways. As Kansas further becomes involved with the locals’ production of their own violent Western, he has to literally fight for his life within the elements of that film’s production. The cinematic violence becomes a reality, and Kansas is shot in actuality for the sake of a “scene” within that film. Hopper himself being from Kansas, and very much exposing himself with his film as he was also exposed in The American Dreamer, had to fight for his life to release this film in the shape he desired.

After the monumental success of his debut Easy Rider, Universal proposed a plan to champion visionary directors and give them $1,000,000 and carte blanche to make the film they desired, and this was one of them. However, upon release, despite receiving an award at the Venice Film Festival, audiences and critics panned the film and it flopped. Some enjoyed it, but most hated it and found it too confusing. A couple years later, it showed up in drive-ins, re-edited and released as Chinchero and ultimately became forgotten. Largely seen on a horrible VHS rip, the film finally was released to home video in its original form, but after the death of Hopper himself.

Within the film, Kansas goes on a self-imposed exile after the death of the fellow stuntman and the set. He remains in Peru with his lover and gets involved with American ex-patriots and a plot to search for gold. In reality, Hopper went on a creative exile in Hollywood after the release of this film. While he appeared in multiple low budget productions in Europe, his enthusiastic return didn’t come until 1980 when he stepped in as director of Out of the Blue which he also acted in. After a stint in rehab, he was cast in David Lynch’s seminal Blue Velvet (1986) and his career was fully revived once more. But within The American Dreamer, Hopper gives this anecdote of driving down a long stretch of highway, with the wind blowing his car. He was driving against the wind so long that he had forgotten he was making a deliberate effort. So when he passed by some grain silos which provided pause from the wind, his car veered into the ditch. Coupling this anecdote with Hopper’s experience during and after his production of The Last Movie, Hopper sees the human ability to produce art as a constant struggle. Whether worth it or not, the filmmaker has to fight against the natural elements, corporate greed, audience anticipation and box office returns.

At a certain point, Kansas becomes involved with a priest from town, who has set up shop in the chapel made for the film set. He attempts to return the solace of God to the villagers who have taken to reenacting gratuitous violence, and he muses, “I hope that when this game is over, morality can be born again.” This brings an interesting point in incriminating the violence apparent in American cinema, and the global effect it may or may not have had. The blurred lines between the cinematizing and real reenactment of violence is apparent. However, this is Kansas’ livelihood. His life’s work is called “a game” by the priest and in truth, the making of a film is treated as a game by the locals as well. It’s a faith play, a celebration of their religion through humor and joy. Men are readily available to throw actual punches for the camera, ready to be shot and hung for the sake of this game they call “filmmaking”. For Hopper, his films are his life, his art. But their value is denigrated to box office numbers and critical praise. The value doesn’t extend any further than that and it feels as if the bile Hopper feels for the studio system came out in that instance.

The most famous moment in the film comes when Kansas and his lover Maria drive his truck into town. They have a conversation but all of a sudden the image cuts to a title card stating “Scene Missing.” The sound continues but we’re left with nothing but our imagination to fill the gap as to what has occurred. Similar moments come towards the end, where we get an extended sequence of a cowboy sitting on a roof, boom mic visible and the slate for The Last Movie itself cuing the start of the film. Hopper as the storyteller becomes a character within the film itself and is at the whims of the filmmaking form. The film doesn’t end until the piece of leader film at the end of the print itself stating “End!” appears on screen. Kansas lived the film that he was making and ultimately gave his life as a result. Hopper put his whole spirit into this film and its failure shaped the course of his life.

How would this film fit within the context of the Western as a form? Considered an acid western like El Topo, this film is undeniably a Western but without the character archetypes and narrative points to hit. It trades El Topo’s concern for Eastern philosophy with European inspired, contemporary American deconstruction of the storytelling form. Hopper’s and Kansas’ manifest destiny is the ability to continue telling a story, sharing their experience and truth with the audience abroad. Kansas is a true cowboy, through and through, a horse wrangler the likes of Randolph Scott in The Tall T (1957), he seizes his opportunity to colonize the village of Chinchero with his divine display of filmmaking and ultimate retribution at the hands of the people. Post-The Wild Bunch westerns will often concern themselves with the morals and logic of the manifest destiny and the abuse of the indigenous Americans. Although done in a roundabout way, these two films approach a metaphorical analysis of this concept that allows the future of Western filmmaking to explore the more abstract.

El Topo was watched as a digital copy purchased on ITunes, The Last Movie was watched on the Arbelos blu-ray release, and The American Dreamer was watched on Amazon Prime.