Heavens’ Gate

Written by Mario Martin 8/28/2024

“If the rich could hire others to do their dying for them, the poor could make a wonderful living”- Cully

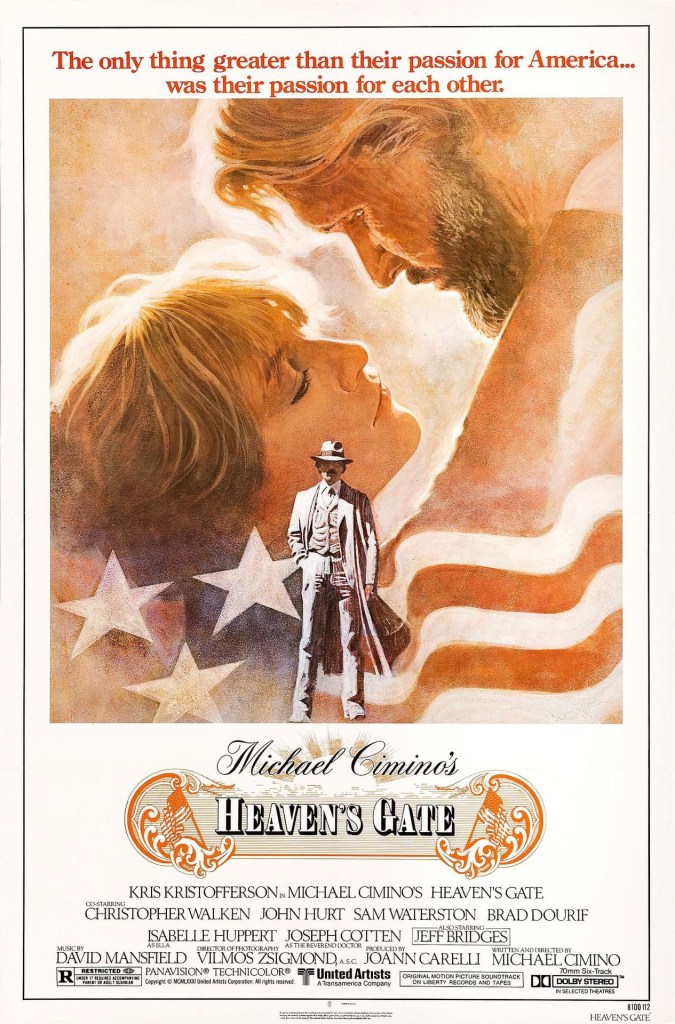

Michael Cimino’s 1980 Western epic, Heaven’s Gate has as much depth behind the story of its conception as the narrative of the film itself does as well. Cimino’s follow up to his legendary Vietnam epic The Deer Hunter (1978), his epochal western was already in production as The Deer Hunter was having its praises sung at the 1979 Academy Awards. Given carte-blanche and a sizeable budget, the lengthy production was rife with controversy due to Cimino’s authoritative behavior, numerous recuts, and tales that include having to rebuild an entire city street to be 6ft wider, as well as being behind schedule by five days on the sixth day of shooting. Despite this, the film endures today both in its states of controversy as well as legend.

The film was a critical and commercial failure, was recut, and severely bankrupted United Artists who distributed the film. Cimino had initially turned in a five and a half hour cut that the studio demanded be severely cut. Ending on a three and a half hour cut, the studio trimmed it further after the disastrous opening weekend. Additionally, some consider Heaven’s Gate to be the death of the director-led New American Cinema movement, a shift back towards the studio maintaining control over the production of films, as well as the death of the mainstream studio western (which soon proved to be false with a string of Best Picture winners in the 90s being Westerns). However, the context of this film is incredibly important in how it was received and lived on, with its retroactive praise coming relatively recently with the screening of the director’s cut at the 69th Venice Film Festival in 2012.

The film itself is concerned with a conflict between immigrant homesteaders and wealthy cattlemen in 1890s Johnson County, Wyoming. More than that, the film portrays the injustices committed against the impoverished immigrant community in the name of capitalistic gain. The Stock Owners Association wishes to incriminate the immigrants for stealing their cattle. They know that the financial loss of that stolen cattle is insignificant, but they want to enforce some sort of law and order out of principle, calling the Eastern European immigrants “criminals and anarchists.” As such, they hire a small army of mercenaries to hunt down the names of nearly 150 people accused of stealing or handling stolen cattle. Those 150 people make up nearly the entirety of the Johnson County homesteaders.

Admittedly, Cimino had taken some artistic liberties with the retelling of this factual conflict. The three central characters, Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson) Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert) and Nate Champion (Christopher Walken) were not in historical truth the people that were portrayed on screen. Averill in the film is a sheriff who involves himself in the conflict between the immigrants and the cattlemen, Ella in the film is a bordello madam caught in a love triangle between Averill and Champion, and Champion in the film is a murderer and an enforcer for the stockmen. In reality, Averill and Ella were murdered by stockmen two years before the conflict portrayed in the film, and Champion was a rancher nicknamed “king of the rustlers” because of his resistance against the stockmen claiming all unbranded young cattle as their own. Champion may have never met Averill and Ella. However, this film goes beyond the historical accuracy and Cimino weaponizes his liberties to elevate the moral quandaries of the film to such a high degree. The empathy elicited for the trio as well as the immigrants central to the film really paints the themes of the film in such a necessary way. It’s a shame that the film with its anti-capitalist musings was released during the dawn of the Reagan administration.

It’s well known that America after 1981 underwent a major conservative cultural shift. Consumerism was at an all time high with mall culture, pop music dominated the charts and the kinds of films that did well in the box office were blockbuster action films and eventually the films of the likes of John Hughes that generally focused on the lives of upper-middle class suburban white families. While it’s certainly not my intent to disparage the pop culture of the 80s to make a point about a film about the evil inherent in capitalism, the fact that Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) came out a few months later reveals a lot about why a film like Heaven’s Gate failed at the box office and in the eyes of critics.

My good friend Jason (returning from my post about The Searchers) made an observation that I will paraphrase to the best of my abilities. His observation was about the success of Francis Ford Coppola’s gangster epic The Godfather (1972). Despite it being treated as a mature art film by the studios and the collaborators involved, its mainstream success skewed the studios’ perceptions of the box office draw of a “mature art film”. Heaven’s Gate was very much a mature art film in the years of the blockbuster. The initially $11m budget got quadrupled by Cimino and his meticulous eye to detail (among many other things) but the type of film Heaven’s Gate was meant to be did not marry well with what the studios expected from its performance. Admittedly, I’m bringing up a lot of claims without addressing too many of them but I promise I will. To describe this impressive cinematic feat to the best of my abilities, I need to put all my cards on the table and go from there.

Similar to what I said about The Last Movie (1971), to try to describe the film narratively would be foolish. For its almost 3 ½ hour run time, the film contains far too many narrative details I could focus on but that’s not at all the significance of the film. With this blog I wanted to contextualize the Western for the time in which the film was made, and its place within the grander pastiche of the form, whether “the Western” itself is a genre or more than just that.

For one the film starts off in 1870, five years after the end of the American Civil War. In the interview with Cimino available with the Criterion Collection release of the film, Cimino identifies this trend of commencement speeches after the Civil War being about “reconstruction and unifying under a singular american identity.” The film starts with Averill graduating from Harvard, the commencement speech being a call to action for all of these educated, high class white men to go forth and share their knowledge and wisdom with the rest of the nation. For the type of film this is, it’s very aware of the class and racial privilege placed upon these men. They’re in a position to make massive changes and have influence on the goings on of the nation, and they’re all higher class white men.

“It’s getting real dangerous to be poor in this country”- J.B.

The significance of this point is the film is so concerned with America’s capitalist history, but absent from the film are Native Americans and the many racial “minorities” that the American national identity was constructed on the backs of. This doesn’t necessarily present an issue, as the conflict central to the film is less so about the colonial history of the nation. However, there is a case to be made that many westerns are about the civilized east colonizing the wild west with their barbed wire fences and railroads. Similar to the settlers who saw “wild, untamed land” and took it for themselves, ignoring the natives already living on the land. Similar to the manifest destiny and westward expansion in the 19th century. The government already recognized areas of land as “Indian territory” but homesteaders disregarded these treaties and staked their claims wherever they desired. The history of America isn’t victimless, and this chapter set in the 1890s is about those Eastern European immigrants.

We’re introduced to Nate Champion when he guns down a slavic man speed butchering a stolen cow. His silhouette behind a tarp, his face is revealed through the hole torn through the tarp with his shotgun blast. He’s introduced as a savage killer, and at a later point in the film as he interacts with another immigrant man, the man asks Nate something to the effect of “why do you hunt us when you look like us?” The strife within this film is between the descendants of immigrants with a strong nationalist identity, and the 1st generation immigrants they try to dismiss as “other than” them. The hypocrisy apparent in this conflict isn’t specific to this time however, as immigrant relations in America is always a hot topic whether it’s 1890, 1980 or 2024. The greed of the stockmen to pursue these immigrants with a death list over some sort of capitalist principle of insuring your losses is also something that remains relevant to our modern late stage capitalist society. While it may not be so literal as stolen cattle and stockowners, living and working in Las Vegas has revealed a mirrored version of this capitalist wasteland.

Relevant to today, the casinos on the Las Vegas strip as well as many food service, customer service or labor intensive work is built off of the backs of immigrant labor, some employers even exploiting the illegal status of some immigrants to circumvent labor laws and work them overtime without overtime pay. Restaurants are quicker to throw out food at the end of the night than give it away to those in need, with the consequence of taking home leftover food often being termination of employment. There are those who will make the argument that disallowing food to be taken home by the workers at the end of the day prevents food from being wasted during the work day. But this argument is so contextual and exactly the argument made by the stockowners in this film. If we don’t make an example of the cattle thieves, then we MAY suffer worse losses in the future. Disregard the human right to feed your family, these barons can’t afford to lose even a single cattle.

It should be no surprise that a film like this with Marxist sympathies on the criminal history of industrial/colonial America appeals to me on a fundamental level. Convenient or maybe even backwards depending on your perspective, that such a film was made with such a high budget in an art form that is so fundamentally materialistic and capitalist. Especially in America, a film is often conceived with the hopes of a box office draw. This was the case in the 80s and is especially the case now. There’s even a case to be made that the invention of cinema in 1895 was also intended as a vessel for escapist art. As such, I had mentioned that a friend of mine identified the box office success of The Godfather as a potential obstacle in the reception of Heaven’s Gate. By this point in cinematic history, we have already seen the genesis of the blockbuster with Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Lucas’ Star Wars (1977). These films presented easily accessible narratives with little obstacles for the general audience. They were well made films that pulled in an incredible amount of box office earnings. Meanwhile, we had films like Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) and King of Comedy (1982) that flopped terribly. Even his legendary cinematic achievement Raging Bull (1980) barely pulled in a return. But the American film industry was back to a point where box office was all that mattered when calculating the value of a work of art.

When assessing the critical reception of the film upon release, there’s a lot of disagreement on the climate surrounding the release of the film. The outpouring of negative reviews were militant, with some calling the film a waste of time and even more recent critics considering the film as one of the worst films ever made. Heaven’s Gate had its support in the 80s however, names like Robin Wood, Martin Scorsese and David Thomson sung their praises about the film. Peter Biskind with his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls talked about the film’s excesses, and mentioned it alongside Spielberg’s 1941 (1979) and Warren Beatty’s Reds (1981) as big budget projects that had a troubled production or less than warm reception. Biskind claims that the backlash against Heaven’s Gate could have easily been directed elsewhere and that there may have been bias against Cimino himself when critics considered the film. But as time could tell, significant works of art such as this film will leave an indelible impression and won’t fade away so easily.

With the Western, there’s an interesting dynamic where a lot of them are concerned with the change in the times. Industry and capitalism follow the homesteaders and the cattlemen westward, and many films will concern themselves with the lone gunman or cowboy reconciling with the fact that they aren’t needed anymore. Barbed-wire fences and railroads create boundaries that box in the wild freedom of these people and the wild west ultimately becomes “tamed.” Interestingly, Heaven’s Gate introduces Averill as a wealthy Harvard graduate, who after a twenty year time jump, is shown to be the sheriff of Johnson County. We don’t know much about Averill’s past before Harvard, so it’s uncertain if he was a country boy with a big opportunity or if he fell into that role by some sort of desire or circumstance. He later in the film claims that he came to the county to fight for the peoples’ rights, but it’s clear that he’s not entirely accepted.

But presenting this problem of the cowboy vs the “civilized” east is important because it’s the full circle of Averill’s story. He gave up his privileged life in the east to be sheriff of Johnson County, leaving his high society wife behind and cohabiting with Ella Watson, the madam of the bordello. She clearly loves him and he buys her gifts and other expensive things. It feels like the option for him to totally inhabit this western life is there, but his eastern life is what holds him back. He still has that wife back home, he has the class obligation, at some point he even gets called out for “… being rich. You only pretend to be poor.” He toes the line of living this free western life but still has the east pulling him back. This works to his benefit at times however. As the wealthy stockmen association put out the kill list of all of the impoverished immigrants accused of stealing cattle, Averill has enough pull to be able to act as a voice for the people (to no avail mind you as the vote to put out the kill list was unanimous.) To complicate the situation however, Ella Watson is on the kill list for allegedly accepting stolen cattle in exchange for sexual favors (the real Ella was murdered by the stockmen for this exact accusation), so it’s questionable where Averill’s priorities lie. Does this kill list present more of a problem for him because of the number of people on it? Or, does he have more personal interest in it because Ella’s name is on that list? The film doesn’t explore this question of interest all that much if at all, it’s just noted that Averill is distraught to find Ella’s name on that list. Although, when thinking about Averill’s obligations to his class and to the eastern way of life, it brings up a conflict of interest as to whether he’s truly defending the livelihood of these immigrants for the right reasons.

However, Averill throughout the film advocates for the people. He speaks out against the cattlemen, and will open dialogue with his citizens even if they ultimately ostracize him for his involvement with these stockmen or for his lack of being able to defend them. A further conflict of interest comes when Nate Champion comes to Johnson County and is shown to be familiar to the citizens, namely Ella and Averill. Despite gunning for the stockmen and having the kill list, he claims he didn’t know about Ella’s name on the list. This conflict of interest arises when Nate, often a john that Ella services, proposes marriage to her. Averill, not yet knowing that her name is on the list but knowing that the mercenaries hired by the stockmen will soon invade the county, wants Ella to leave. Ella wishes to stay however, acknowledging that Nate had proposed when Averill didn’t. Averill has the privilege of being able to send her east for her protection, but her heart is truly in the west, and she doesn’t want to leave.

With the love triangle center to the film, it’s interesting to interpret the three individuals as images reminiscent of different American ways of life. Ella is obviously the working immigrant who was able to stake her claim and find success, Nate has the face of a European immigrant and even though he’s literally in line with the stockmen and eastern capitalism, he is more of the image of the cowboy or outlaw of the wild west. Despite Averill being the sheriff of the county and inhabiting the image of the West, his obligations keep him in the east. However, Ella at a point in the film questions why she’s not capable of loving both men. For the immigrant workforce in America, the ability of a marriage between their success and the capitalist system of the country should be available, but capitalism wants more from the immigrant workforce than they’re able to provide and as a result they’re chewed up and spit out by the system. [Note: this is an idea I will return to later on.]

But with Averill’s obligations to the east, the people of Johnson county ostracize him, with the mayor even firing him from his role as sheriff. When the mercenaries hired by the cattlemen invade, the citizens of the county mobilize to meet the mercenaries on the battlefield and fight for their lives and their rights.

With Champion’s obligations, he confronts the leader of the Association and severs his ties with them, choosing to no longer be their tool. This proves fatal as Champion holes up in his cabin with a couple of his acquaintances, and the mercenaries come for him. He’s gunned down and the cabin burned down but before his death, he writes a letter to Ella and Averill professing his love, affection and commitment to both and details his heroic end. The black-clad “evil” gunman of western myth has his heroic redemption and becomes an image of legend. However, so does the livelihood of the wild west. The west has been conquered by the east and now they’re moving forward to exploit the impoverished immigrant workforce.

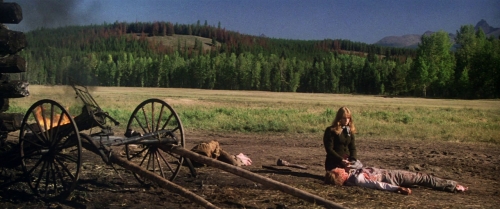

Ella and J.B, the local saloon owner played by a young Jeff Bridges, lead the citizens of Johnson County to the battlefield to confront the mercenaries in a deadly battle. Averill stays out of the way, drinking and grieving what he perceives as the loss of the conflict on his own. With this first stage of the conflict, the first wave of mercenaries are for the most part taken out, with the citizens grieving the lives lost and recouping their additional losses. Averill eventually gathers himself, with the help of the others who have stayed behind to avoid the fighting, and saddles up to join his people on the battlefield. He finds Ella grieving at the body of Champion and reads her the letter that Nate left behind. The two then meet the rest of the townspeople where Averill brings his eastern education to craft Roman siege weapons to be used in the next conflict. With the mercenaries receiving their reinforcements and the villagers with their siege weapons, the final conflict arrives.

“They advanced the idea that poor people have nothing to say in the affairs of this country”- Mr. Eggleston

Bloody and brutal, both sides suffer their losses, with a man on the Association’s side furiously watching the battlefield and crossing off names on the death list. Even then, the lives lost on the townspeople side were simply tallies on a bigger list. The epic final conflict of the film comes to a halt when the U.S. cavalry arrive to stop the conflict. They claim they’re there to take the mercenaries back east to be tried and punished for their murder spree but Averill calls out, “you’re not taking them home, you’re saving them.” The “civilized” east came to protect their own, offering now reparations or solace for the citizens who were hunted and lost their livelihoods. They’re simply told, go home. With bodies strewn across the dusty battlefield, this statement comes as a shock to all those who survived the conflict. Just, “go home.”

A woman in the throes of shock puts her pistol in her mouth and takes the only way out she knows. The conflict is over and they may have technically won, but there was nothing for them to win in that conflict. The absolute non catharsis of the battle is evident with the wide master shot of the battlefield that shows the destroyed siege weapons and the mercenary blockade, numbers of unseen faces just turn and walk away. This is the truth of American history, no conflict won was really an accomplishment for those involved. Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse won at Little Bighorn, but look where we Natives are at now. The immigrant workforce may have “won” that conflict, but look at how the disparity between the upper class and working class is still evident if even more distant today.

This point is severely punctuated by the penultimate scene of the film. Having buried Champion; Averill, Ella, and J.B. exit the cabin to all of a sudden be halted by the remainders of the Association who without warning gun down Ella and J.B. Averill returns fire but it’s too late. Ella, the image of the immigrant workforce in the film, has also been conquered by the capitalistic “civilized” east. The image of the West in Champion, and the image of the immigrant workforce in Ella have been destroyed. All that’s left is for the east to continue their conquering of land west of them, “from sea to shining sea.” With Averill left behind, he simply gives up.

We transition to the final scene, set another 10-15 years later. Averill is back east, on his boat off the coast of Rhode Island. He enters the cabin of his yacht to find his wife, the same girl he met back in Harvard, dysthymic and strewn motionless on a chaise lounge. She asks for a light, with Averill producing his lighter and moving in to light her cigarette. The look in his face isn’t joy, it certainly isn’t peace. He grieves what he left behind, he grieves that through everything he just returned east, where he feels he doesn’t belong. With this final image of his motionless wife, it provides an interesting comparison. In her essay “Western Promises” available in the Criterion Collection release of the film, Giulia D’Agnolo Vallan paints the West as well as Ella as always in motion, ever moving. Ella is incredibly dexterous on horseback, the scene where Champion loses his life shows Ella jumping from her wagon onto the back of her horse when the reins were severed. When Averill gives Ella that carriage in the beginning of the film, she pushes it to a manic speed with Averill pleading her to slow down. She moves between Averill and Champion at her convenience and is only still once she is killed. This image of the wild west and this wild woman juxtaposes with the stillness of Averill’s eastern life, as well as his wife. She lays still and lets Averill come to her to light her cigarette. In the west, with endless chances and opportunities for the homesteaders and immigrants, life is always in motion.

Under capitalism, life is stagnant. We may be in a time crunch, always rushing to make it to work on time, rushing to meet deadlines or production goals, but our lives go nowhere. Our spirits are crushed, and we too are at the whims of the capitalist system. Averill’s spirits are crushed, and even though he was a transplant image of the wild west, his goals were destroyed and he must live out the rest of his life playing the role of the eastern aristocrat. Always, dreaming of his life in the west, it was simply over for him and for this dream of those seeking opportunities.

Heaven’s Gate was viewed on the Criterion Collection blu-ray release

REFERENCES:

D’Agnolo Vallan, Giulia, “Western Promises.” Criterion Collection, 2012.