Straight Shooting and Hell Bent

Written by Mario Martin 9/4/2024

“I thought that you were better than the other. But now I see you’re not” – Bess Thurston in “Hell Bent”

For this month on TUMBLEWEEDS I wanted to spotlight the first westerns of some of the form’s most iconic filmmakers. So while my goal is still relevant of contextualizing these films with the times in which they were made, as well as their place within my theory of Westerns as a form rather than an explicit genre, this month I’m also looking at these films for how well fleshed out the creative voices of these filmmakers were from the start, as well as how these films may have introduced the audience to themes or patterns recognizable in their later works. For this month, I’m looking at; John Ford’s Straight Shooting (1917) and Hell Bent (1918), Samuel Fuller’s I Shot Jesse James (1949) and The Baron of Arizona (1950), Sam Peckinpah’s The Deadly Companions (1961) and Ride the High Country (1962) as well as the first episode of his TV show “The Westerner” (1960), and then finally with Monte Hellman’s Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting (both 1966). Interestingly, with the exception of Hellman these films were also these filmmakers’ directorial debuts.

By introducing Straight Shooting we immediately arrive at an interesting dilemma. It’s a small surviving part of John Ford’s vast work in silent cinema, and as is the case with his filmography, most of silent cinema has been lost or destroyed. That can be attributed to simply the loss of any or all prints, this misuse, the pattern of studios recycling the prints for the silver halide crystals used to produce nitrate stock (the cost saved by this practice wasn’t a whole lot to be honest) or by one of the many studio fires that has happened that destroyed entire catalogs of historically significant films. Two of these fires include the 20th Century Fox fire of 1937 and the MGM fire of 1965. These fires led to the destruction of most of the studio’s original nitrate prints (as nitrate was highly flammable) with one of the most popular cases being the loss of the original print of London After Midnight (1927) a famous role for the legendary Lon Chaney that survives only in press photographs and on set stills. Turner Classic Movies put out a reconstructed version of the film in 2002 that used the original script and numerous film stills to recreate the original plot. However, the film in its original format is lost.

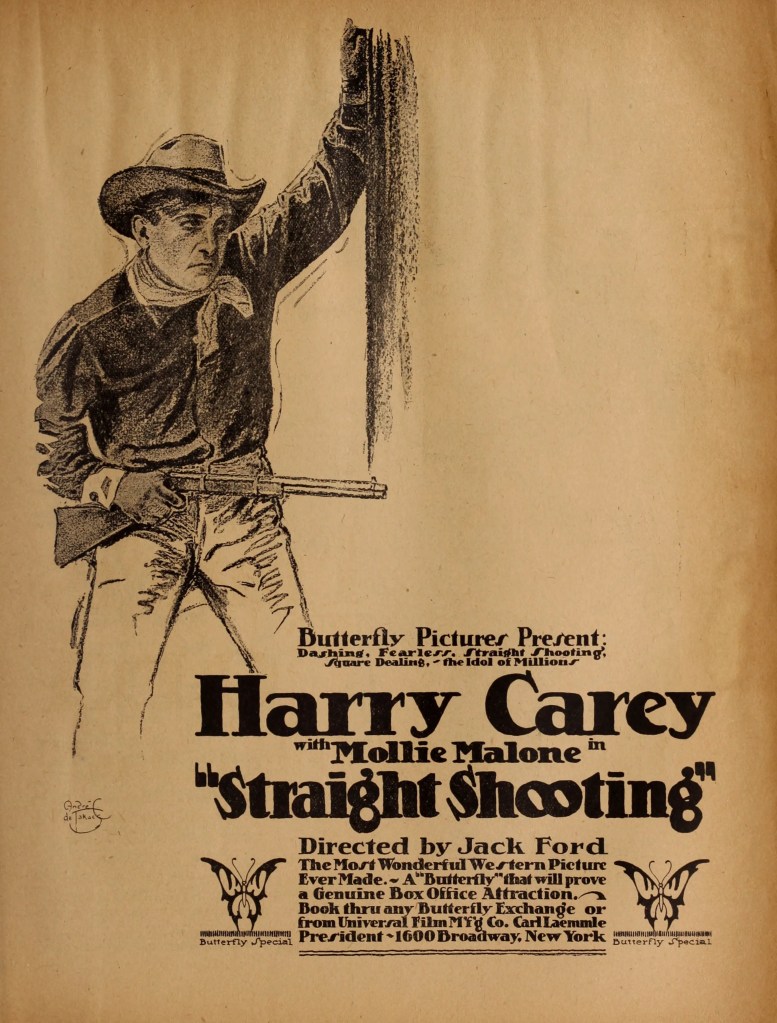

Such is the case with most of John Ford’s silent filmography under Universal (who had their own fire in 2008 that destroyed numerous audio masters) and as a result, his true directorial debut with the short two-reeler The Tornado (1917) is lost as well as the string of other two-reelers or three-reel “quickies” made up until he directed Straight Shooting. These two-reelers include films like The Trail of Hate, The Scrapper, Cheyenne’s Pal, and The Soul Herder (all 1917). This of course is a shame considering Ford would have already had extensive practice before his feature length debut so not being able to see them is personally painful for that reason. But I digress. Also, for those who may not already know, a reel of film will hold about 1,000 ft of 35mm film which equates to about 10 minutes in runtime. So a two reeler will run about 20-25 minutes while a three reeler would be somewhere from 30-40 minutes. This is important for later. What is also important is that John Ford’s The Soul Herder was his first collaboration with one of Universal’s biggest stars Harry Carey. This collaboration would bring the duo 25 films of work together as well as a string of films with Carey as the Western folk hero “Cheyenne” Harry, the star of both of this week’s films.

When we go back this far into cinematic history, film was still a relatively new art form. John Ford (initially going by Jack Ford) was the younger brother of Francis Ford, whose legacy goes back to 1912 with the two-reeler “Custer’s Last Fight” which he directed and starred in. Francis Ford started his Hollywood career working with Thomas H. Ince who is widely considered the “Father of the Western.” At a certain point, Francis realized that Ince was taking credit for work that Francis directed, so he moved over to start working with the newly founded Universal Film Manufacturing Co. From here, Francis would cast “Jack” Ford in his films to do stunt work or other acting. Additionally, Francis would mentor Jack in filmmaking form and when the time came for Straight Shooting to enter production, Francis recommended Jack to direct the film once the original director left.

There’s a story behind the production of this film that it was initially budgeted to be a two-reeler by Universal, but John Ford and Harry Carey concocted a wild plan to turn it into a five-reel feature length film by claiming that rolls of exposed film had fallen into a river. When Ford and Carey turned in a feature length film, studio exec Carl Laemmle allegedly said “if i paid for a suit and got an extra pair of pants, I wouldn’t just throw them away.”

What’s also historically significant is that these films are unequivocally Westerns. They were billed as such, and follow all of the boundaries that we recognize with the form. Hell, most of the iconic images were established with these films. But the significance is that I feel that a lot of what goes into considering the Western as a genre is attaching a sense of antiquity or nostalgia to those films. Many contemporary Westerns feel incredibly modern, and these silent Westerns were so close to the times in which they’re depicted that they’re almost documentary in context. Don’t forget that Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) is set only five years before Straight Shooting was released. Many of the folk heroes of Western lore were still around. The legendary lawman Wyatt Earp of O.K. Corral fame didn’t pass away until 1929. Pat Garret who famously took out Billy the Kid didn’t pass until 1908, with outlaw Butch Cassidy allegedly dying that same year. Although John Ford was born in Maine to Irish immigrant parents, and gained his nickname as fullback of Portland High School, “Bull” Feeney (Feeney was his legal surname) Ford grew up with the rustic know-how that seems iconic to the heroes of the west. This upbringing endeared Carey, who was a professional cowboy at some point in his life. So with the setting of Straight Shooting being the tail-end of the 19th century being so close to the reality of these mens’ lives, it hardly has any element of nostalgia or antiquity and rather serves as an outlet for telling a compelling narrative.

With that said, Straight Shooting is set ambiguously after the Civil War, and concerns itself with the conflict between the free and violently selfish cattlemen and a homesteading family taking advantage of their opportunity to lead a new life. A narrative that may sound awfully familiar if you read last week’s post on Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980). The conflict at play here is the barbed wire fences and railroads of the organized east vs. the free roaming cattle drivers of the Wild West, the kind to make their own laws and enforce it on outsiders. As mentioned in previous posts, a lot of Westerns will be about the incoming colonization of the “civilized” east taking over the west, and the people living in the wild west lamenting the loss of their ways of life through assimilation into industrial, city life. However, this film puts its sympathies with the small homesteading family and how they’re at odds with every element of the Wild West, including the people. However, this film also presents a moral dilemma for the outlaw protagonist that shows up multiple times in Ford’s pictures, but I’ll arrive at that dilemma later.

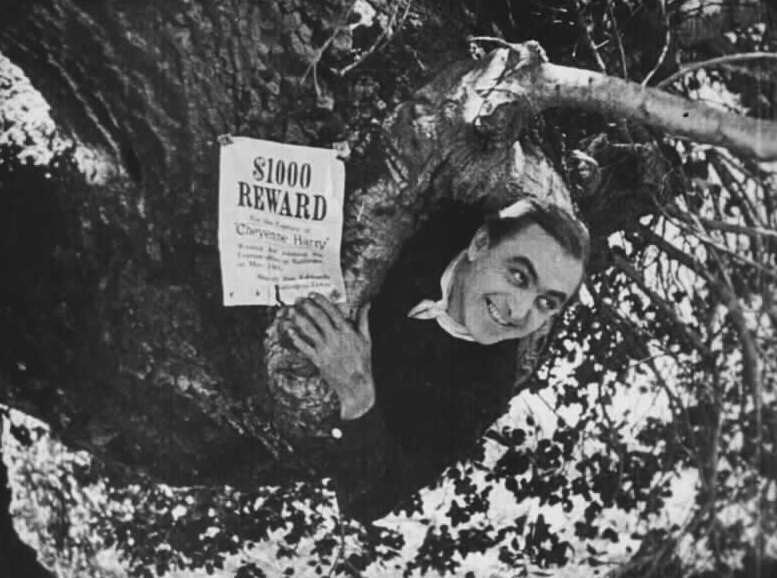

One ever present theme of Ford’s westerns that shows up in this one is the unreliability of people’s loyalties. Namely in this film, “Cheyenne” Harry is hired by “Thunder” Flint, the leader of the cattlemen to chase the homesteading Sims family off of their land. Harry is wanted for a robbery, and crosses paths with not only the town sheriff but also a bounty hunter out to get him. However, Harry buys the hunter a drink and they immediately become the closest of friends. They drunkenly chase off one of the boys related to the Sims family and although they hold their pistols to each other, not quite trusting the other’s intentions, they resume their drinking. Harry has no personal stake in this conflict between the cattlemen and homesteaders, he’s just being paid to do a job. As such, his loyalties lie with the coin and has no need to deviate from that.

The general conflict of the film is in regards to the cattlemen trying to drive the Sims family off their land, but one action they do to initiate the central conflict of the film is setting up fences around the river, claiming that the Sims family will be shot for trespassing. One day, when the son of the Sims family goes to fetch some water, he’s gunned down by Flint’s men. The Sims family grieves and buries the body, but this is when Harry drunkenly happens upon them, gun drawn. But once he sees the young Joan Sims (played by Molly Malone), he refuses to take their life. His morals are questioned and he claims that while he can do a dirty job, this one in particular is just too dirty for him. With this, his loyalties change to protect the Sims family.

With this change in loyalties, Harry goes back into town where he’s confronted by his bounty hunter drinking buddy. Also hired by Flint to chase off the Sims family, he now knows that Harry doesn’t wish to gun for that gang anymore. Formally, an interesting element is presented in the succeeding gunfight between the two men. As the two men draw their guns and march towards each other, John Ford chooses to iris in on their eyes in a stylistic gesture that has become all the more famous in more recent westerns. This iris technique is caused by applying a filter to black out the image, leaving just a small circle to capture the image. This technique produces something similar to an extreme close-up to the actors’ eyes which develops all the more tension within the scene. From the start, John Ford was already a master at keeping the audience invested.

Naturally, the bad man turned good survives the standoff, and acknowledges that with Flint on the way to invade the Sims family he too must ride off. He recruits a gang that he used to run with, and the epic climax arrives. With the Sims family holed up in their house, fighting off the Flint gang in a standoff that would come to be seen in everything from Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) to the murder raid in the super recent epic saga from Kevin Costner Horizon: An American Saga (2024). By fighting off the Flint gang, Harry ostensibly saves the day but is offered the opportunity to stay behind to help the Sims family. Joan has fallen in love with him and the patriarch “Sweetwater” Sims laments the death of his last surviving son, offering Harry a place in his home to fill that void. In a further test of loyalty as well as an introduction of personal stakes to an otherwise neutral man, Harry promises to return the next day with his answer. He rides off and finds a spot to introspect. This moment of introspection becomes a massive motif throughout the entirety of the Western form, the free range outlaw/cowboy who must choose between security behind boundaries or being able to live free on the outskirts of the law.

What’s interesting here is that allegedly the initial cut had an ending where Joan finds him and asks his answer, and he chooses to leave. In the version we got, she finds him and he embraces her, professing his love for her while lamenting his forfeit of the wild life he has led. Nevertheless, this theme of the wild man saving the girl and giving up his life for that eastern “civility” is seen in many of Ford’s later films such as the aforementioned Stagecoach and My Darling Clementine (1946). It is clear that the hero of this film is deeply flawed, as are the heroes in all of Ford’s films. I mentioned in my post about The Searchers (1956) that Ford tackled the heroic myth making of the Wild West with John Wayne’s character Ethan. Now, I find it compelling that Ford from the start was already tackling this notion that the mythic heroes of the “Wild West” were not perfect. Cheyenne Harry is a troubled alcoholic with questionable morals and even more questionable loyalties who comes to a position to do some good, but as seen in the next film Hell Bent (1918), there almost seems to be a necessity for those types of “heroes.”

Before I talk about the next film however, I would like to address the fact that John Ford had directed another feature length Western in 1917 titled Bucking Broadway. Another Cheyenne Harry film, with Molly Molone returning as the love interest (albeit a different character) I chose to pair Straight Shooting with Hell Bent which was released in 1918. Bucking Broadway is available as a special feature on the Criterion release of Stagecoach, but this week’s two films are released together through Kino Lorber. Fact of the matter is, the physical release is paired together and the two films are often talked about together especially considering they were rediscovered before Bucking Broadway. The story of this week’s two films is that they were considered lost (as I had mentioned is the case for most of Ford’s silent work as well as most of silent cinema to start with). However, the last surviving prints were rediscovered in the Czech Film Archive, translated and tinted, and the restoration process started from there. These prints were discovered at some point before the turn of the century although a color print showing the awful tinting was made in 1993, so it’s reasonable to believe the films were rediscovered at some point before that while Bucking Broadway was not rediscovered until 2002.

Regardless, the interesting thing about silent cinema is that a lot of exposition is found through the text of the intertitles. The intertitles could be changed to affect the tone of the film either subtly or obviously. As detailed in the essay that comes with the Kino Lorber release of Straight Shooting, there are two distinct versions of the film. With the Museum of Modern Art’s version of the film, translated from the Czech print itself, Harry’s change of heart seems to come out of a change in morality. In this translation of a translation, Harry tells Joan, “Now I can see those boys as they really are. Thank you for opening my eyes.” When he swears disloyalty to Flint at the saloon, he says “I’m reforming. I’m quitting Flint, quitting killing.” In the MoMA version he’s more decisive, telling Sweetwater when he proposes that he marries Joan, “Me a farmer? No. I belong on the range.”

Whereas in 2016, Universal made a digital restoration of the Czech print, but used a continuity treatment for the film’s working title Joan of the Cattle Country. In this version, rather than a total moral shift, Harry’s change in character comes from distaste. The same quotes from before are now shown as, “I’m kind o’ sick of this job, girl, since I seen all this … Tell Flint that him and me are through. There’s some jobs too dirty even for me – n’ this is one of ‘em.” Rather than the decisiveness shown in the MoMA print, in this Universal version Harry is more reactive or even passive, his proclamation of “I’m going straight” is now shown as “Somethin’s happened inside o’ me – so I’m goin’ straight.” With the exchange directed towards Sweetwater when suggesting marriage to Joan, Harry now says, “You’re a settler, old man, so you can’t understand the little voices that are always callin’ and callin’.” Me mentioning all of this is simply out of interest in how much a character can change when considering how the intertitles are handled. Universal Harry is reactive and blames powers outside of his control for how he is, while MoMA Harry is direct and straightforward, knowing who he is but still willing to give up the live he has lived for the love of Joan in the end. Which makes his development more heroic? Making a conscious decision to go straight or simply being confronted with the ugliness of his way of life and not wanting to remain in that place? Nevertheless, I digress.

With all this talk of good bad men, Hell Bent starts with a metatextual prologue where an author is receiving a letter from a reader of his most recent tale. The letter expresses desire to see more tales of bad men put in a good position, as good men doing good deeds simply isn’t realistic. From here, the camera moves towards a painting of a saloon brawl on the author’s wall, and transitions into the film itself. Cheyenne Harry returns and flees the brawl he started by cheating at a game of poker. Once safe from the town, we see the drunken Harry toss out all of the stashed cards in his pocket and takes his winnings and rides off to his next mark, a stash of gold set aside in the town of Rawhide.

The female lead in this film is Bess Thurston, played by Neva Gerber. Bess’ brother works for Wells Fargo but is unable to support her, so she seeks employment as a dancing girl at a saloon (a position that can almost be seen as a modern stripper). Harry finds himself at this dancing hall in Rawhide where once again, he finds a drinking buddy in a man called “a bad man with a soft heart. But only in some places.” Cimarron Bill is his name, played by Duke R. Lee (who played Flint in Straight Shooting), and he and Harry drink and fight over the last remaining bed in the saloon. An almost slapstick episode with Harry riding his horse into the room, feeding it straw from the pillow, and throwing Cimarron Bill out the window who returns with his pistol drawn to then proceed to throw Harry out the window. Despite this, the two remain compatriots throughout the film, especially once Beau Ross (Joe Harris) makes advances towards Bess.

Narratively, the film continues with Bess’ brother Jack assisting Beau in a robbery, where Beau kidnaps Bess and rides into the desert. Harry chases after them, and a gun battle ensues where both Beau and Harry are wounded. They give Bess the surviving horse to ride back to town, while the two wounded men journey through the sandstorms raging through the desert. The storm takes Beau’s life, while Harry survives and is found by Cimmaron Bill. He’s taken back to town where he lives happily with Bess. With that being the literal retelling of the narrative, this film continues the themes Ford shows in his preceding film, themes of questionable loyalty and of the wild man going straight for the love of a “civilized” woman.

As in Straight Shooting, Harry is introduced as a drunkard and a schemer who’s only motivation is money until he is faced with love. Harry’s loyalties (more so personal priorities in this film) change to accommodate this love he has found with Bess. But another element present in this film that is also present in many Westerns is the motif of man vs. nature. Many westerns concern themselves with the protagonist being stranded or having to suffer the elements of nature to reach their next goal. In The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (1966), Blondie and Tuco have to trek a hundred miles through the barren desert, in El Topo (1970) the titular character has to scour the desert for the four master gun men. With this film, Harry has to brave the sandstorms of the desert to make his way into the arms of Bess. Trudging side by side with Beau, not only is it a competition to see who will win the heart of Bess, but also to see who is the bigger man. Harry’s last trial of strength as the wild outlaw is to suffer through the elements to find security and comfort in the love of Bess. This also presents the general theme of challenged masculinity ever present in westerns. Man vs. man, man vs. the elements, and man vs. destiny are themes that show up in many if not all Westerns and are themes that Ford masterfully demonstrates in two of his first westerns. A legacy that he continues throughout his entire career, Ford would also go on to be a major inspiration for many filmmakers across the board. Accepted as an auteur by the french critics of the New Wave, admiration for him would be expressed by the likes of Ingmar Bergman, David Lynch, Akira Kurosawa, and a multitude of other filmmakers either inside or outside the form of Westerns.

Straight Shooting and Hell Bent were watched in their respective Kino Lorber blu-ray releases

REFERENCES

Gallagher, Tag. Untitled, Kino Lorber. 2020.